The white nationalist violence in Charlottesville, Va., on Saturday was about a lot more than a statue, but the statue is where this specific event began. It’s a depiction of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, erected in 1924 in a place of honor in a city park.

Videos by Rare

Today, many people in Charlottesville want this statue and others like it gone. They argue it’s a monument to white supremacy, oppression and the violence of slavery and the Civil War. Their critics contend that to remove the statue would be to erase heritage and history, and prominent among those critics are the self-avowed Nazis, KKK members and other racists who marched in the city this past weekend.

Now, given these two choices, my sympathies are entirely with the pro-removal side. Still, I’ve come across three other options for dealing with this sort of (rightly controversial) statue, and I think they could individually or in combination offer a better way, one that doesn’t whitewash racism or hide the past.

RELATED: Here are three things we must remember when we talk about Charlottesville, race and free speech

1. Move the statues to a more appropriate location.

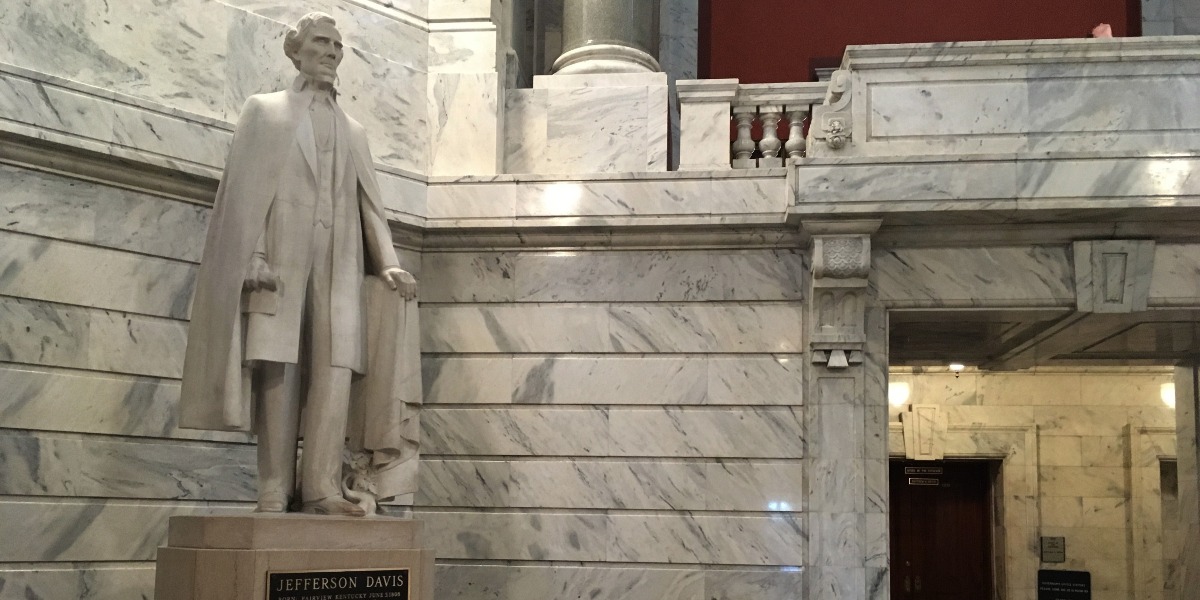

This is perhaps the easiest solution, and it’s already being used to handle some Confederate statues. In Baltimore, for example, city officials have decided to relocate statues to Confederate cemeteries. Some statues from New Orleans may be moved to appropriate historical museums to be part of exhibits chronicling the history of slavery, the Civil War or the Jim Crow era.

This option might not work for very large statues, but where possible it could be a good way to help museum-goers visualize historical figures and understand government’s endorsement of and participation in racial oppression in American history.

2. Use the statues in new art with new meaning.

Alfredo Stroessner was a dictator who ruled the Latin American nation of Paraguay for several decades in the 20th century. He had political critics tortured and murdered, rigged elections and was generally so oppressive that his government was dubbed the “poor man’s Nazi regime.”

After Stroessner was ousted, Paraguayans understandably didn’t want statues honoring him in their public spaces. Here’s what they did with one of them:

Here's what Paraguayans did with a statue of dictator Alfredo Stroessner (1954-89). It's an interesting compromise. pic.twitter.com/gEtUPLseDz

— Laurence Blair (@laurieablair) August 16, 2017

RELATED: The South must arrive at the decision to remove Confederate monuments on its own

You don’t have to know much about art to get what that statue communicates about the Stroessner regime. It’s an effective way to denounce historical abuses while maintaining an awareness of this painful history.

3. Put the statues in context in a “fallen monument park.”

Many former Soviet countries have been thinking about how to deal with statues of people like Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin for a lot longer than we’ve been having this Confederate statue debate. One solution they’ve developed in Russia, Hungary, Lithuania and Estonia is to create a “fallen monument park” that puts the statues in context.

The context happens in two ways. First, “Each monument includes a plaque explaining when it was erected, how it was funded and that it has been preserved and installed in the park not to celebrate Stalin or Lenin or their ideas but because of its historical significance,” writes Radley Balko, who visited the fallen monument park in Moscow.

And second, the old statues of the Soviet leaders are accompanied by new statues of their victims. In Moscow, Balko says, “One statute of Stalin stands — minus its nose — in front of a harrowing sculpture depicting dozens of human heads stacked behind barbed wire. It’s a monument to the victims of totalitarianism.”

Here in the States, a fallen monument park could collect Confederate statues, removing them from places of undue honor, and give them a similar context. We could have signs explaining the relevant history as well as memorials to the victims of slavery and postbellum racial oppression. These options won’t satisfy everyone, of course, but for the bulk of people who want to reject racism while remembering history, they could do the trick.