Well, the world didn’t end.

Videos by Rare

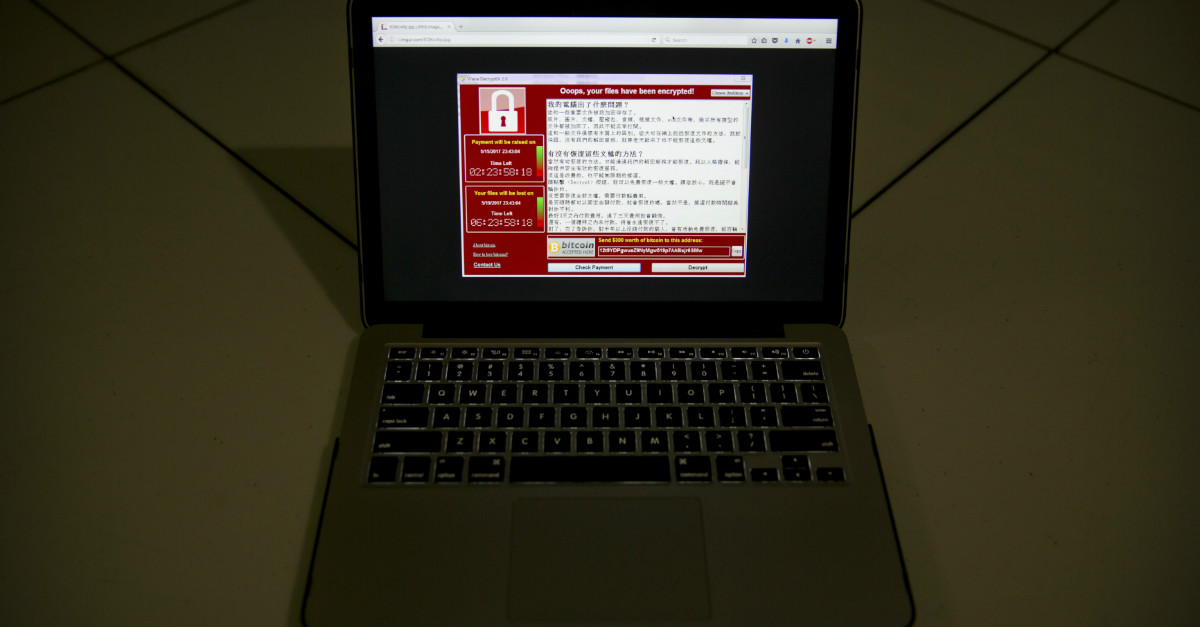

The ransomware attack that affected over 200,000 computers in over 150 countries across the globe and forced some British hospitals to turn away patients didn’t render the nation-state obsolete or plunge the globe into anarchy, and governments and tech companies seem to have stopped the bleeding.

We do, however, owe it to ourselves to ask how this happened. In addition to inspiring a lot of horrible movie plots, issues of cyber security (or “the cyber” if you’re President Trump) can sway elections and cripple essential services. Perhaps most frighteningly, cyberattacks can strip citizens of their privacy, whether directly in the form of theft of personal data by hackers, or indirectly by government intrusion in the name of security.

In this case it was a little of both.

The ransomware program, “WannaCrypt,” was originally developed by the National Security Agency before being stolen and publicly released by the hacker group that calls itself Shadow Brokers, because apparently this organization is run by the “Fate of the Furious” screenwriter who thought it would be a great idea to name Charlize Theron’s cybercriminal character “Cypher.”

This is the case of the government literally putting weapons into the hands of cyberterrorists. In a blog post published last Sunday, Microsoft Chief Legal Officer Brad Smith said that an “equivalent scenario with conventional weapons would be the U.S. military having some of its Tomahawk missiles stolen.”

Smith went on to call for a “Digital Geneva Convention” that would require “governments to report vulnerabilities to vendors, rather than stockpile, sell, or exploit them.”

RELATED: 5 ways to become a smaller target for ransomware hackers

In this case, the NSA figured out a way past Microsoft’s security and tucked it away for a rainy day only to have it stolen by hackers. Fortunately, in this case Microsoft found the chink in their armor on their own and fixed it with a patch released in March. Only those organizations that had failed to install the patch were vulnerable to the ransomware attack, which blocked users from accessing vital documents and demanded $300 in Bitcoin to unlock them.

If Microsoft hadn’t discovered the problem and released the patch, this could have been a lot worse.

If I see that the lock on my neighbor’s back door could be picked with a bobby pin, the responsible thing to do would be to tell him, not keep the information to myself in case I want to break into his house someday. Sure, I might be able to get inside and help if there’s an emergency and he’s not home, but I’m also leaving his family vulnerable to burglars, kidnappers, and rapists, and ignorant of their own vulnerability.

If he trusts me, he can leave me a key for emergencies, but he should never have to.

Smith’s call for governments to stop undermining cybersecurity brings to mind an earlier incident in which the tables were turned and it was the government pressuring a tech company to compromise its own encryption.

In the aftermath of the 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack, politicians on both sides of the aisle found themselves divided over Apple CEO Tim Cook’s decision not to comply with a federal court order that Apple create a “backdoor” or “key” to help the FBI open San Bernardino terrorist Syed Rizwan Farook’s iPhone and, potentially, anyone else’s iPhone, too.

Trump and then-president Obama sided with the FBI, as did Florida Senator Marco Rubio, although he initially supported Apple.

John Oliver even devoted an episode to the controversy and took an uncharacteristically even-handed approach before coming down on the side of encryption and personal liberty. Oliver asked his audience to consider what might happen if Apple was expected to comply with similar demands from the governments of nations like Russia and China that “have as much respect for privacy as horny teenagers in ‘80s comedies.” He warned that the U.S. government can be like your dad: “If he asks you to help him with his iPhone, be careful because if you do it once you’re going to be doing it 14 times a day.”

The recent ransomware attacks have shown us exactly how dangerous these “backdoors” can be.

The best way to protect ordinary people from cyberattacks is for governments and tech companies to trust each other, and that trust cannot be built in an environment of deception and compulsion. There will always be high-pressure moments, but both parties should be able to agree that on the whole, good cybersecurity makes everyone safer.