The movie Senator Rand Paul said should be “mandatory for Congress to watch” premiered on Friday. At its best, it pushes absurdity to the point of poignancy, offering a stinging rebuke to those legislators who seem, as Paul put it in a Facebook post, ”hell bent on continuing/restarting the war in Afghanistan.”

Videos by Rare

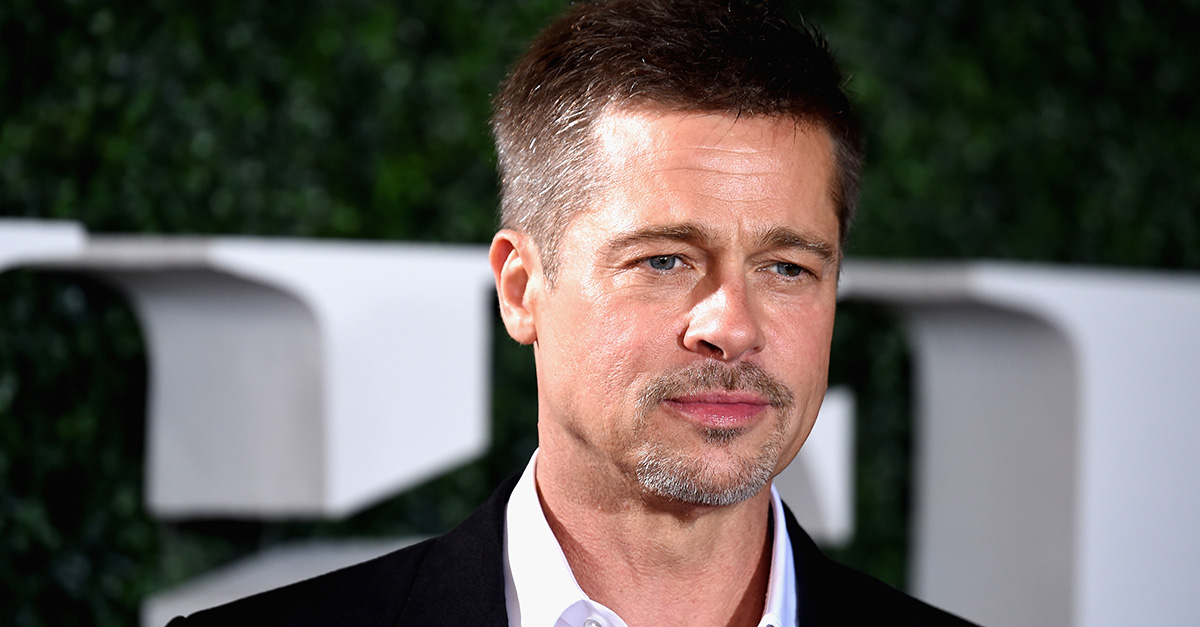

“War Machine,” a Netflix original written and directed by David Michôd, opens with General Glen McMahon (a thinly-veiled stand-in for Stanley McChrystal played by Brad Pitt) striding confidently through an airport on his way to assume command of coalition forces in Afghanistan. (Proceed with caution: Spoilers are ahead.)

As Pitt wordlessly communicates the general’s bullheaded tenacity, the narrator intones “Ah, America… What do you do when the war you’re fighting just can’t possibly be won in any meaningful sense?”

The rest of the film is spent answering that question, and in the end, things come full circle. McMahon/McChrystal is sacked after an embarrassing Rolling Stone article and the film ends with his replacement striding confidently through an airport on his way to assume command.

“War Machine” displays a variety of influences, from the farcicality of “Dr. Strangelove” to the tense urban combat of “American Sniper,” but it is most clearly patterned on “The Big Short” (2015), which told the stories of Wall Streeters in the months leading up to the housing market crash (and also featured Pitt).

The two movies follow the same basic pattern: present an absurd and unsustainable situation, explain it in the simplest possible terms, introduce the characters working within that situation, bring the whole thing crashing down, and then explain to the audience how we’ve failed to learn our lesson.

RELATED: On Memorial Day, let’s remember that America is overdue for a foreign policy debate

The narrator, a Rolling Stone reporter named Sean Cullen standing in for his real-life counterpart Michael Hastings on whose book the film is based, gives us a brief overview of counterinsurgency tactics and concludes that “it doesn’t really work… You can’t build a nation at gunpoint.”

The film abounds with pithy cynicism like that, mostly coming from a State Department official named McKinnon who observes that “All the winning we were ever gonna do, we did in the first six months” and that there will be “no street parade at the end of this one.”

Against that cynicism stands McMahon’s bold assertion that victory is possible despite his total inability to articulate what victory will look like.

In the film’s best scene, McMahon stands in front on an absurdly complicated flow chart attempting to persuade the German government to send more troops. “In the math of counterinsurgency,” he says, “10 minus two equals 20,” explaining that killing two insurgents would cause 12 more spring up in their place. It’s easy to see why Sen. Paul loved this movie.

McMahon has “a fetish for completion,” and he embraces the task set before him, but it’s obvious he would be more at home in the pitched battles of symmetrical wars long past. In speeches, he insists that the end goal is the protection and betterment of the lives of the Afghan people, but when his pet offensive gets bogged down, he snaps at his men to “Kill the mother***ers! Eat ’em alive!” in an outburst reminiscent of Kurtz’s “Drop the bomb. Exterminate them all” in “Apocalypse Now!”

In the end, the cognitive dissonance demanded of McMahon by his impossible position begins to take its toll. Early in the film, it’s easy to laugh at catch-22 statements like “surely a result is the best possible outcome,” but by the time the film reaches its climax, it is no laughing matter.

RELATED: Missing from Donald Trump’s Brussels speech: NATO’s longest war

After a group of Marines accidentally kill an Afghan child, McMahon extends his hand, a hand that Cullen says is “bent into a permanent claw, like it was still clutching a World War II cigar” to the bereaved father and says “I assure you, this is the hand of helping. This is the helping hand.”

The villagers respond, “Please leave now.” From that moment on, McMahon’s spirit is broken, and when the Rolling Stone article reports his staff’s drunkenness and criticism of President Obama, McMahon seems almost relieved to be fired.

“War Machine” suffers from flat supporting characters, an uneven tone, and some questionable script decisions, but with the help of Pitt’s driven performance, it sends a powerful message.

It asks us as Americans whether we could look into the face of an Afghan father whose son was killed by a stray grenade and explain why it was all worth it. If we can’t, perhaps we have no business being there.