We all know the chorus to the Beatles’ strangest song. But what do those weird, fantastic lyrics mean? Maybe John Lennon didn’t want his fans to figure it out. “I am the Walrus” was written by Lennon and credited, like most Beatles songs, to Lennon–McCartney. It was released both on the B-side of “Hello, Goodbye” and on the Magical Mystery Tour album. Before its soundtrack was released as a record, Magical Mystery Tour was a Beatles film that premiered on BBC television in 1967.

Videos by Rare

The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour

As the title, taken from the musical’s first song, suggests, this slice of Beatles cinema skewed heavily psychedelic. Following the trippy sonic experimentation of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the Beatles continued to infuse their work with colorful LSD experiences. The premise of Magical Mystery Tour actually derived from Bohemian legend Ken Keysey’s adventures aboard his famous school bus called “Further.”

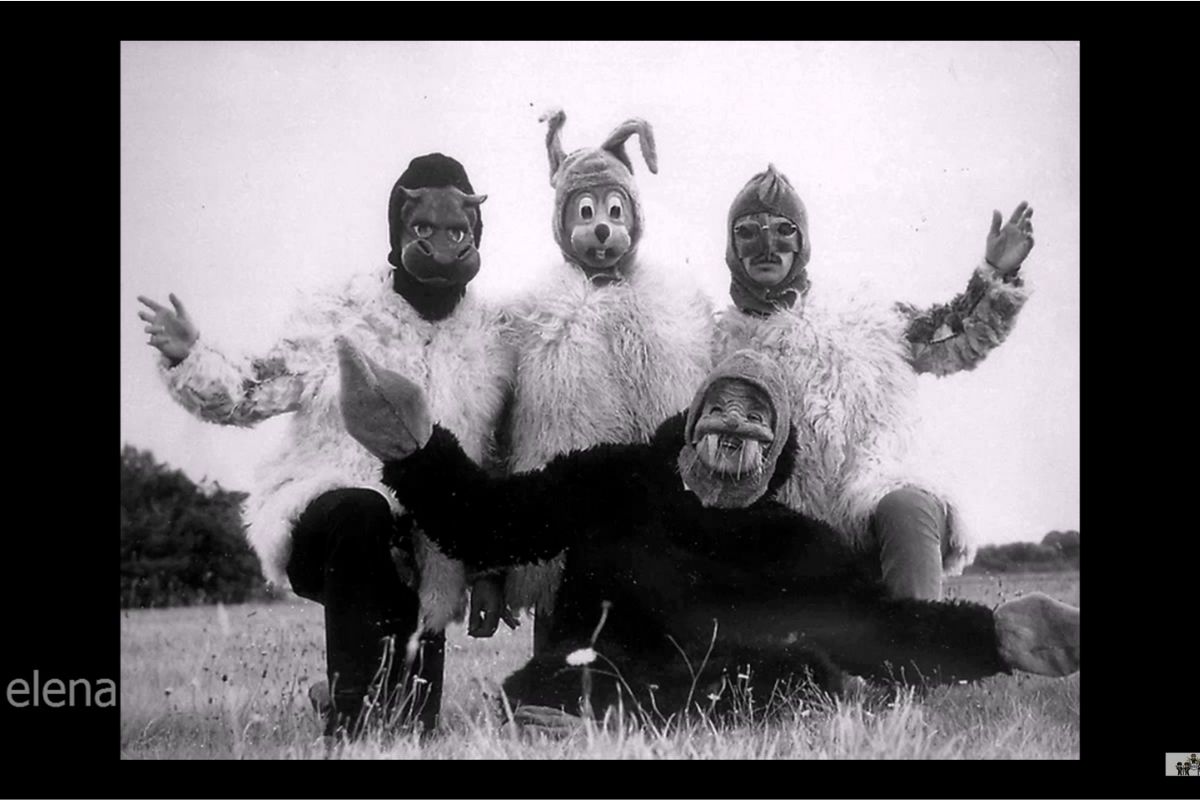

During the 1960s, the writer Ken Keysey stood in as something of a transition between the older beat generation and the free love hippies that followed. Traveling cross-country on a communal, multi-colored school bus with his rag-tag group of friends (nicknamed the Merry Pranksters), Kelsey’s adventures represented the ultimate alternative lifestyle. Channeling that hallucinogenic zeitgeist, Magical Mystery Tour followed the story of a coach bus (much like the coach busses that traveled between Liverpool and the Blackpool Lights) on its surreal encounters. Ringo Starr played the protagonist. John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and (again) Ringo Starr portrayed the group of magicians wreaking havoc on board.

“The Fool On The Hill” By The Beatles

In the tradition of Ken Keysey’s beat background, Magical Mystery Tour was highly spontaneous. Mostly unscripted, the band members were left to improvise antics. Critics were not amused. Paul McCartney was panned for spearheading the project and left to publicly defend himself. Reflecting on the TV special in 1981, socio-musicologist Simon Frith called it boring and “willfully inexplicable.” It seems that rather than defining the times, in this instance, the Beatles buckled under the aesthetics of a larger social movement. But even if their third film missed the mark, its original songs (later compiled onto the Magical Mystery Tour EP) went on to captivate — and confound — the world. These include “Fool on the Hill,” “Blue Jay Way,” and “I am the Walrus.”

“I Am the Walrus” By The Beatles

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NYXqT49g5Dw

By 1967, the Beatles had established themselves as artistic luminaries. As such, every line in a Beatles song is read closely and studied obsessively. Even today. John Lennon himself declared that he composed “I Am the Walrus” to throw off such academic attempts. Lennon said:

“The words didn’t mean a lot. People draw so many conclusions, and it’s ridiculous. I’ve had tongue in cheek all along — all of them had tongue in cheek. Just because other people see depths of whatever in it… What does it really mean, ‘I am the Eggman?’ It could have been ‘The pudding Basin’ for all I care. It’s not that serious.”

And yet, we are going to put it under the microscope anyway. Luckily, many aspects of the “Walrus” songwriting process have been publicized over the years. Apparently, the intro was inspired by one of John Lennon’s early acid trips.

See how they run, like pigs from a gun,

see how they fly

I’m crying

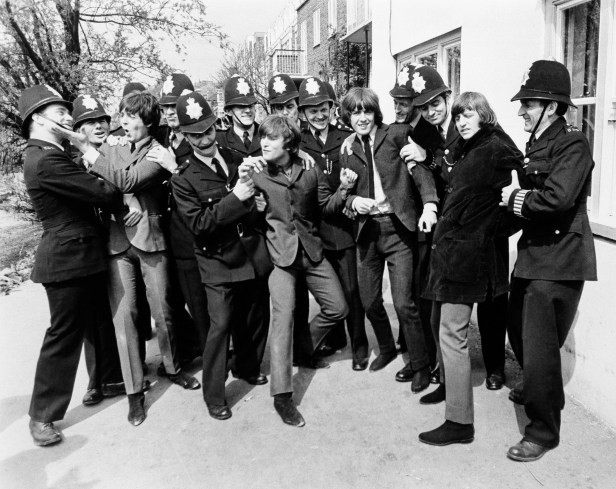

These first lines came to John Lennon while he was tripping and heard a police siren. The swinging beat of the song channels the continuous pulse of the siren. The later lines, “Mister City policeman sitting / Pretty little policemen in a row” — some delectable alliteration — trace back to this private moment of Lennon’s when he was so overcome by the intrusive sound.

“Mister City Policeman Sitting / Pretty Little Policemen In A Row”

Yellow matter custard

Dripping from a dead dog’s eye

John Lennon consulted with his high school friend Pete Shotton to come up with this verse. Shotton recalled a particularly nasty nursery rhyme about “green slop pie” which became so key to “I Am the Walrus.” Of course, the lines that followed, “Crabalocker fishwife, pornographic priestess / Boy, you’ve been a naughty girl, you let your knickers down” were an adult addendum.

Like a photographic collage, every verse of “I Am the Walrus” weaves in another of John Lennon’s personal callbacks. Some are simple; the “English garden” was really his own English garden. And while knowing where the lines come from is helpful, it doesn’t quite illuminate how or why they fit together. Lennon himself explained that the “elementary penguin” was meant to be Allen Ginsberg who “went around chanting Hare Krishna” — although this sounds suspiciously like an eye-roll toward his own bandmate George Harrison, the noted Hare Krishna believer. In those moments, the lyrics read like a comprehensive 1960’s polemic. But overall, it’s just a bunch of non-sequiturs layering to stoke a poetic quality. As if held together by some dream logic. For Lennon alone, that dream has distinct meaning; it is assembled from his own memories. But to listeners, a double meaning may occur. This is most evident in the song’s (somewhat) impenetrable chorus:

I am the egg man

They are the egg men

I am the walrus

Goo goo g’joob, goo goo goo g’joob

Goo goo g’joob, goo goo goo g’joob, goo

John Lennon was an avid fan of Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland. Lennon’s “egg man” could easily represent Humpty Dumpty, a character that was also present in Alice in Wonderland. Fulfilling the Alice theme, the book’s sequel, Through the Looking Glass includes a poem: “The Walrus and the Carpenter.” (Watch the 1951 Disney animation below.) Carroll’s stanzas tell the story of a walrus and a carpenter walking on the beach. They happen upon a bed of anthropomorphic oysters which they eat, hungrily. The walrus voices some sympathy for the small creatures, whereas the carpenter merely complains about the meal: “The butter’s spread too thick!” In the end, however, the walrus eats even more oysters than the carpenter. Upon hearing this tale from Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, Alice remarks that “They were both very unpleasant characters.”

Walrus And The Carpenter

Although “The Walrus and the Carpenter” has come to be read widely as an allegory, Martin Gardner, the foremost Lewis Carroll scholar, cautions that not every aspect of the Alice books carries intentional symbolism, as they were written specifically to jog the imaginations of children. Gardner’s stance is not unlike the various remarks from John Lennon about The Beatles’ over-analysis. In Lennon’s lyrics, the Carroll reference dissolves (practically) into utter baby talk: goo goo ga joob. And yet it’s impossible not to wonder how Carroll’s story of “The Walrus and the Carpenter” fits into the arch of “I Am the Walrus.”

“The Ballad Of John And Yoko” By The Beatles

Just days before he was assassinated, John Lennon, along with his wife Yoko Ono, were interviewed by David Sheff for Playboy magazine. In the revealing (and historic) piece of journalism, Lennon admitted that when writing “I Am the Walrus” he had not yet noticed Lewis Carrol’s capitalist critique; a Marxist reading which came to dominate his own interpretation. He said:

“Later, I went back and looked at it and realized that the walrus was the bad guy in the story and the carpenter was the good guy. I thought, Oh, shit, I picked the wrong guy. I should have said, “I am the carpenter.” But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it? [Singing] “I am the carpenter…”

This may seem John Lennon was right when he advised against combing these particular lyrics for deeper knowledge. But his own personal faltering is just what makes “I Am the Walrus” so fascinating to return to, again and again. Who knows what revelation might pop up? But beware: in “Glass Onion” off The White Album Lennon sang, “The walrus was Paul” and while fans momentarily rejoiced in the clarity, this song reveals itself as a deliberate send-off. Get it? A glass onion shatters when you peel back the layers. And as for Paul being the walrus, Lennon told David Sheff, “That line was a joke… I was sort of saying to Paul, “Here, have this crumb, have this illusion, have this stroke — because I’m leaving you.” (OUCH.)

In Conclusion

During the Playboy interview, David Sheff asked John Lennon, “What is the Eighties’ dream to you, John?” Neither could have known that Lennon would not live through the eighties; he would die before 1981 even began — before Sheff’s article even hit newsstands. In response, Lennon said, “Well, you make your own dream. That’s the Beatles’ story, isn’t it? … Don’t expect Jimmy Carter or Ronald Reagan or John Lennon or Yoko Ono or Bob Dylan or Jesus Christ to come and do it for you… That’s what the great masters and mistresses have been saying ever since time began. They can point the way, leave signposts and little instructions in various books that are now called holy… but the instructions are all there for all to see, have always been, and always will be. There’s nothing new under the sun… I can’t wake you up. You can wake you up. I can’t cure you. You can cure you.”

John Lennon shied away from identifying our collective dream. And in doing so, he rejects the concept of a decade as it’s designated in the culture. With humans on their eternal trajectory, nothing can be new. To Lennon — a man who, with a little help from his friends, truly defined the 1960’s — art does no more than offer a faint guide to our own madness. The same goes for politics. The same goes for religion. “I Am the Walrus” is just a bunch of recycled words. So in that spirit, it’s fitting that the song ends with a muffled recording of Shakespeare’s King Lear. There is no greater master. And in his greatest play (in my opinion), Shakespeare tells the story of a foolish king’s mad descent. The verse included in “I Am the Walrus,” lifted from the BBC’s AM airwaves, is actually a death soliloquy. It’s spoken by Oswald, the loyal steward to King Lear’s daughter.

Oswald: Slave, thou hast slain me. Villain, take my purse.

If ever thou wilt thrive, bury my body,

And give the letters which thou find’st about me

To Edmund, Earl of Gloucester; seek him out

Upon the British party. O, untimely Death!

Orson Welles As King Lear

The inclusion of Shakespeare’s text is a mellow note to end on. In the King Lear scene, Oswald is killed by a peasant and laments his fate — whilst making one last request: that the letters he carries be delivered. His desperate plea both embraces “untimely death” and acknowledges one’s sacred duties as a messenger. Lennon displays a comparable (though cynical) attitude in Playboy, as he offers the basic story behind his Beatles’ lyrics while advocating the general resistance of their interpretation. Maybe it was his disillusionment. After all, the Beatles were more popular than Jesus Christ. For a time. But on the brink of the 1980s, those songs must have sounded pretty different from their maker. Still, it’s hard to believe Lennon when he says of his own writing, “It’s not that serious.” It has to be! It still is. John Lennon was murdered 40 years ago this week. And this devastating anniversary has been noted, and mourned, worldwide. Mark David Chapman thought he could kill the messenger, but creativity lives on.

Oompah oompah, stick it up your jumper!