In 1917, historians say 13 soldiers started a riot at the site of Camp Logan, a military encampment, which trained soldiers during the first World War.

Videos by Rare

Many say the group sentenced to death for their actions did not occur fairly, and their present-day descendants want justice.

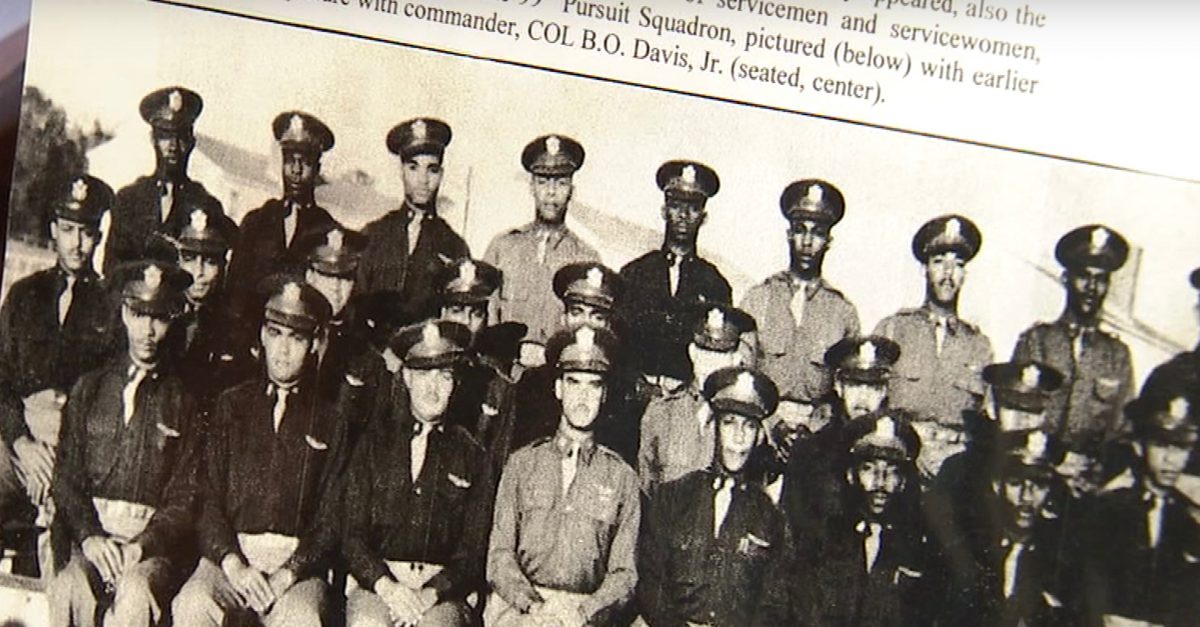

Records show those 13 soldiers fought as part of the Third Battalion of the 24th United States Infantry, a unit made of almost entirely of African American soldiers who guarded Camp Logan during its construction.

The story goes, they rioted because of the racist treatment they endured while stationed there.

RELATED: Following Charlottesville, Houston comes to a crossroads on monuments and marches on the home front

“They sent these soldiers into the most hostile environment imaginable,” Charles Anderson said in an interview on the subject. “There was Jim Crow laws, racist cops, racist civilians, segregated streetcars, and the workers building the camp hated their presence too.”

Anderson said he is related to Sgt. William Nesbit, one of those 13 executed soldiers.

After Harvey, vandals defaced a memorial marker at the former site of the camp in Houston, an act authorities believe to be racially motivated, according to Novara Media, highlighting a reality existing both then and now, nearly 100 years later.

“The soldiers were standing up for America when it wasn’t standing up for them,” Paul Matthews, founder of the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston, said in an interview. “The riot was a problem created by community policing in a hostile environment.”

During their enrollment, before being stationed at Camp Logan, the soldiers reportedly received fair treatment; after they arrived, however, their presence angered white residents:

They saw black men wearing uniforms and carrying guns, black men with military status, and many said they believed their presence would lead other black residents seeking better treatment.

Tensions mounted as segregated streetcars and racial slurs toward the African American soldiers became a norm.

On August 23, historians say the powder keg finally blew, after one of the soldiers, Pte Alonzo Edwards, interfered with the police arrest of an African American woman, local resident Sara Travers.

Reports say police pistol whipped and arrested him for doing so.

When he asked about Alonzo’s arrest, authorities later shot and arrested Cpl. Charles Baltimore, as well.

People came to believe the policemen killed Baltimore, and a mob of angry white people made the move on Camp Logan.

Though this turned out to be false, it still incited a riot, which left 16 dead, five being policemen.

The whole unit incurred a court marshal, and the service sent them back to New Mexico.

All in all, the military decision found 110 guilty, 19 of which they ultimately hanged, and another 63 received life sentences. Many believe those hung never even killed anyone.

Today, descendants of the soldiers say are trying to bring the subject to the public eye and encourage discussion.

Angela Holder, a relative of Cpl. Jesse Moore, said she successfully lobbied the Veterans Association for two gravestones to commemorate soldiers killed in the riot.

And she plans to do more:

“We tried during the Obama presidency for a posthumous pardon and were on the list, but missed out,” Holder said in an interview. “Perhaps we can approach a Texas politician or the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to help.”

RELATED: A new Texas-based poll claims to show how Texas voters truly feel about Confederate monuments