With the summer off from teaching, I’ve been spending a fair amount of time in Beaver Falls, the small Western Pennsylvania town where I lived the first 22 years of my life, and everybody seems to be talking about the opioid crisis.

Videos by Rare

According to city documents provided by my father, who has served as mayor since 2012, there have been 14 overdose deaths in the first six months of 2017 alone.

By way of comparison the entirety of Beaver County, which according to census data has a population of around 170,000 compared to the 8,500 inhabitants of Beaver Falls, suffered no more than 20 overdose deaths in all of 2014.

If the last six months of 2017 are as bad as the first six, Beaver Falls could end up with a proportional overdose rate 30 times higher than the 2014 countywide rate.

And then there’s the anecdotal evidence.

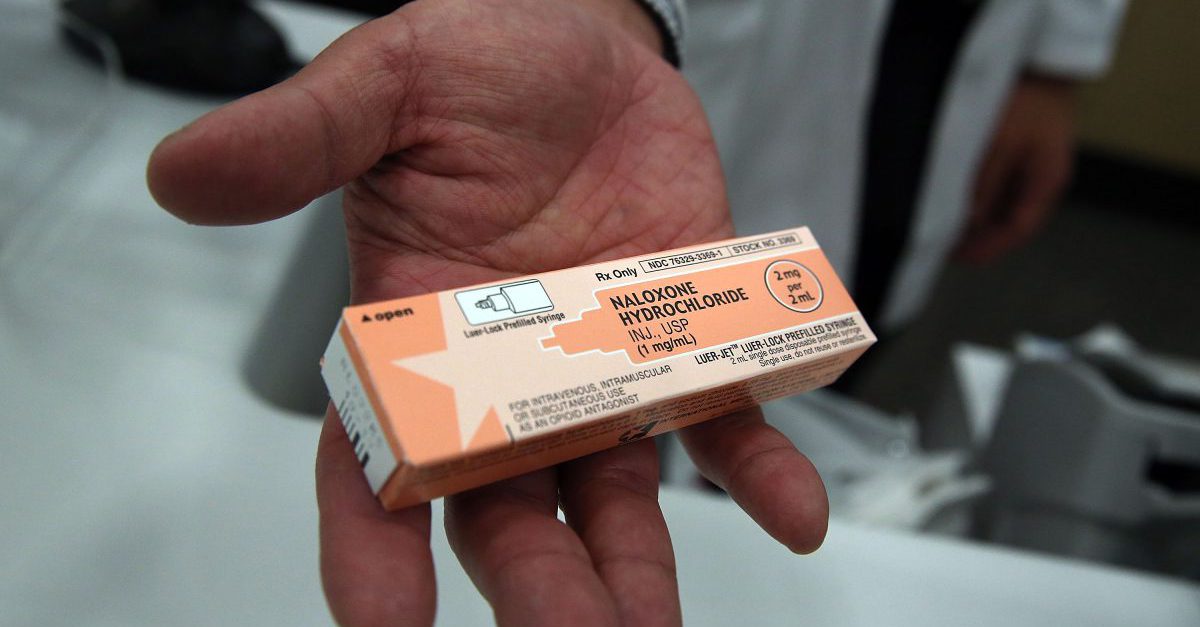

My childhood best friend Nic works as a Beaver Falls firefighter and is often called upon to administer the lifesaving antidote Narcan to overdosing addicts. Nic recently told me that he has revived the same man twice under the exact same circumstances: the man overdosed behind the wheel of his car and crashed it into a building.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of these overdoses is that they’re increasingly happening in public places. The New Yorker recently observed that addicts have begun collapsing “in gas stations, in restaurant bathrooms, in the aisles of big-box stores” as a way to ensure that they will be found and revived before they die.

Many citizens, first responders, and local government officials are growing tired of what they see as a Narcan safety net that forces them to revive the same addicts five or six times only to see them back on heroin within days or even hours.

Last month, an Ohio city councilman proposed a “three-strike” system that would require 911 dispatchers to simply hang up if they received a call to revive an addict who had already been revived twice.

Some of my douchier Facebook friends openly mock addicts with patronizing hashtags like #saynotoheroin and calls to simply “let them die.” And even people I consider kind and rational have suggested that if we stop administering Narcan, the problem will quickly solve itself.

Beaver Falls has implemented a program to try to help revived addicts get clean, but so far it hasn’t saved a single person.

I, too, once scoffed at the idea of treating addiction as a disease. But the more research I do, the more I see that the numbers support that approach.

According to a report by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, sales of prescription pain meds quadrupled from 1999 to 2010 and continued to increase until enough prescriptions were written in 2012 for every American adult to have a full bottle of pills. The same report found that 80 percent of new heroin users started out by abusing prescription pain meds.

It’s easy to see how this happens. Prescription pain meds feel amazing, and doctors are giving them out like candy. A friend of mine reported being prescribed 80 pills for a wrist injury that didn’t require anything stronger than Advil. Other friends have gotten prescriptions after surgery and told me that their parents cut their pills in half or withheld them altogether, fearing that their child would become addicted.

RELATED: Jeff Sessions’ crusade against marijuana hurts the most vulnerable — I would know, I’m one of them

In college, I found myself with a few Percocet left after getting my wisdom teeth out, and over the course of a few weeks I took two or three recreationally. Fortunately, I had a friend—now my fiancée—who told me what a bad idea this was, so I threw the rest of my pills away. If I hadn’t, I worry what might have happened to me.

There is, however, still the possibility of hope.

The rise of medical marijuana could cut down on the over-prescription of painkillers, and a FEE article recently highlighted Oregon’s effort to decriminalize small amounts of hard drugs, freeing up resources to focus on arresting dealers and treating addicts. Similar approaches have already proven successful in Portugal and the Netherlands.

I’m not sure what the long-term solution is, but we can’t just keep throwing Narcan at the problem. We have a moral obligation to save people no matter how many times they need saving, but Narcan only treats the symptoms; we need to cure the disease. This toxic marriage of the War on Drugs with the proliferation of prescription painkillers has to stop.

[protected-iframe id=”ce3858cd91e270c3fdbe3cdcaf0d1af6-46934866-78805695″ info=”https://rumble.com/embed/u76hf.vd8j5/” width=”640″ height=”360″ frameborder=”0″ class=”rumble” allowfullscreen=””]