There are a number of giveaway phrases we libertarians and conservatives have gotten used to hearing that indicate when someone has no interest in limiting government. Perhaps the most annoying of these is “You’re not going to balance the budget by cutting (insert pet cause here)”—no, not alone we’re not, but it’s certainly going to help, so pass the hatchet!

Videos by Rare

Another is “Freedom of expression was never supposed to mean the right to (insert deviant behavior or offensive speech here),” as though the speaker has clairvoyant insight into the mind of James Madison and is aware of First Amendment exceptions that he himself forgot to include.

In Turkey, they were clever enough to include these exceptions outright, particularly when it came to freedom of the press. The Turkish constitution asserts that “The press is free and shall not be censored,” and then spends its next paragraph laying out all the circumstances under which the press might be censored. Turkish media outlets can be prosecuted if they “threaten the internal or external security of the State or the indivisible integrity of the State with its territory and nation, which tend to incite offence, riot or insurrection, or which refer to classified state secrets or has them printed” and coercively suspended if they are “found to contain material which contravenes the indivisible integrity of the State with its territory and nation, the fundamental principles of the Republic, national security and public morals.”

RELATED: After its failed coup, Turkey hurtles deeper into Islamic extremism

Contrast that sinister gobbledegook with the majestic succinctness of our own First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” No asterisks, no qualifiers, no allowances for self-anointed victims hollering about hate speech or politicians pretending state security means making themselves inviolate to criticism.

Yet it’s the Turkish model, not the American one, that’s more prevalent in the world today. The South African constitution, considered postmodern and admired by one Ruth Bader Ginsburg, provides for freedom of expression and freedom of the press, then harrumphs that this doesn’t cover “advocacy of hatred that is based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion, and that constitutes incitement to cause harm.” Imagine what creative lawyers could do (and have done) with that! Britain and Canada also have prohibitions on hate speech, which have led to such lunacies as a dim-bulb reality TV star facing prison time for insulting those with Down Syndrome and a conservative writer hauled before a panel to answer for his criticisms of Islam.

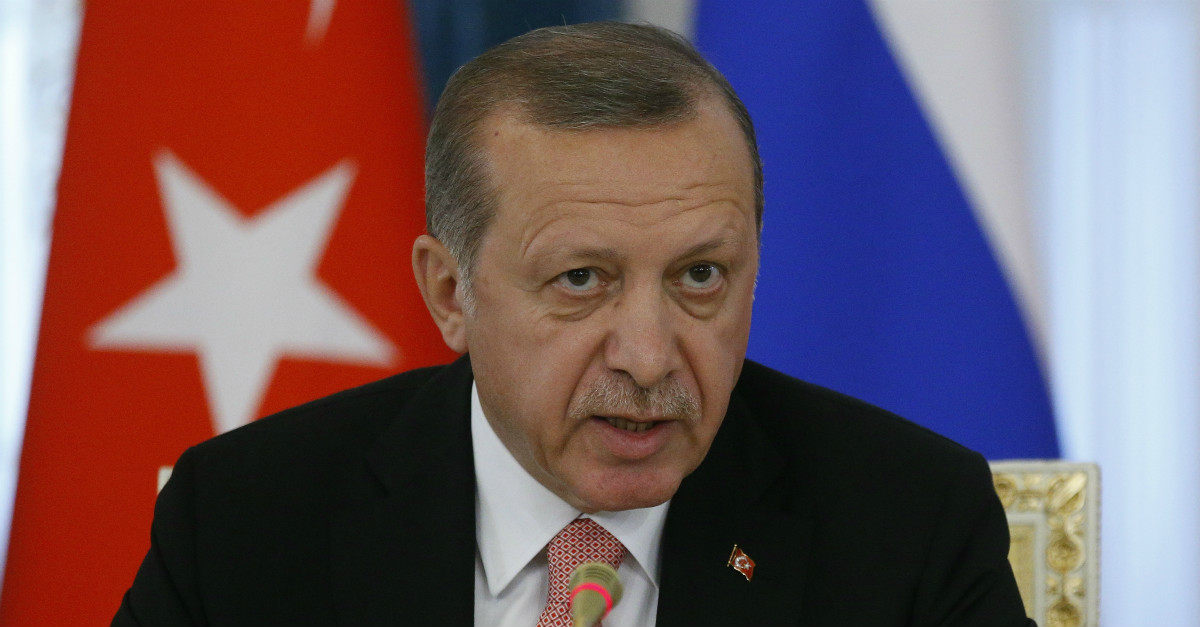

If you give government a loophole, even a narrow one, they’ll find a way to plow a blaring tractor-trailer of censorship right through it. Today, in Turkey, under the anvil-weight of president Recep Erdogan, journalists are being tossed in prison by the score. The reason is allegedly to protect the security of the nation after a coup was mounted last year—and we shouldn’t downplay how jarring that putsch was, with a bomb even hitting the Turkish parliament building. But Erdogan has since used the uprising as a pretext to expand his own powers. Among his first targets were journalists, and around 120 of them are currently languishing in prison.

RELATED: Milo Yiannopoulos and Richard Spencer remind us what free speech is and isn’t

He can get away with that, holding up at least a fig leaf of legality, thanks in part to the gelatinousness of the Turkish constitution’s press protections—that aforementioned exception for those who “threaten the internal or external security of the State.” Turkey was once acclaimed as a model for civil liberties in an oppressive Middle East, and it even modified its laws in 2004 and 2008 to become even friendlier to the press; today it’s a police state, a model for how an autocrat can sprout up in a nominally liberal society.

Bear that in mind the next time you hear someone bleating that the “First Amendment doesn’t mean the right to hate” or citing Oliver Wendell Holmes’ idiotic “shouting fire in a crowded theater” formulation (Christopher Hitchens once began an address on free speech by yelling “Fire!” into a crowded lecture hall several times, only to be met with apathetic silence). Our First Amendment is better off for being airtight. Anything less is a jackboot waiting to fall.