WEST PALM BEACH, Fla. — Sitting in his oceanfront condominium in Palm Beach, Martin Zelman can’t immediately name the president of the United States, isn’t sure what year it is and admits he can’t remember the month or the date of Valentine’s Day.

Videos By Rare

But he knows he wants to divorce his wife, whom he married in 2000, seven years after they began dating.

Or does he?

That is the $10 million question that surrounds Zelman vs. Zelman, a unique and legally complex divorce case wending its way through Palm Beach County Circuit Court.

While the issues raised are intensely personal, they lay bare the ways adult children could use the court system to manipulate prenuptial agreements designed to protect spouses in second marriages. They also expose quirks in Florida’s divorce laws, particularly a little-known caveat that imposes a three-year waiting period in cases where one of the spouses has been declared mentally unfit.

“This is a very unique case. I’ll give you that,” Palm Beach County Circuit Judge Charles Burton said during a hearing last week.

Like many of the messy divorce cases that have played out here, the backdrop, not surprisingly, is money.

On one side are Zelman’s three adult children, who would get their hands on roughly $10 million of their father’s estimated $50 million estate if they can push their stepmother out of the picture before their 87-year-old father dies.

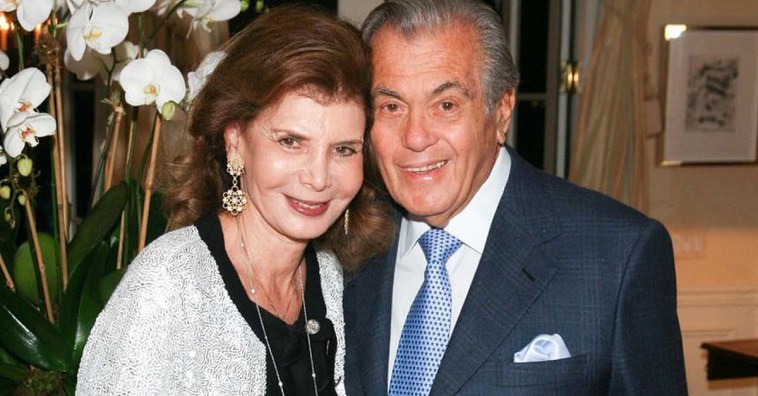

On the other side is Lois Zelman, an 80-year-old former Wall Street stockbroker. She is fighting the divorce because, some say, she wants to pocket the estimated $10 million in cash and property she was promised as part of the prenuptial agreement she signed when she married the wildly successful Long Island real estate investor.

Both sides claim they are trying to protect Martin Zelman, who all agree suffers from dementia. And both sides demonize the other, insisting that if millions weren’t at stake, the other side would walk away.

“If Martin Zelman had no money would Lois still want to be married to him?” asks attorney Joel Weissman, who is representing Martin Zelman in the divorce.

Lois says that’s an easy question to answer. “I was with him for 22 years,” she said. “The money wasn’t the be all, end all. He was handsome. He was charismatic. I married him because I loved him. I still do.”

Her attorney, Jeff Fisher, is equally adamant that Zelman’s children have shredded their father’s marriage out of greed.

Martin Zelman’s son, Robert, scoffs at Fisher’s claims. “It was never about money,” said Zelman, who runs his father’s business in Great Neck, N.Y. “It’s always been about protecting my dad.”

That circuitous path that led to divorce court began last year when Robert Zelman filed petitions in probate court claiming his father was mentally incompetent and Lois was ignoring his needs. He asked that a guardian be appointed to oversee his father’s finances.

After hearing conflicting testimony from friends that described the Zelmans as a loving couple, and caretakers who claimed Lois was abusing Martin, then-Palm Beach County Circuit Judge Diana Lewis found that Lois was a threat to her husband’s well-being. Lewis gave Lois a day to move her belongings out of the couple’s longtime penthouse in the Sun and Surf condominium and into a unit the couple owns elsewhere in the complex.

Further, while Robert Zelman initially asked that his father be declared totally incompetent and all of his rights taken away, he later amended the petition so his father could retain some rights. Lewis agreed that while Martin shouldn’t be allowed to marry, manage property, drive or work, she allowed him to retain the ability to perform some tasks independently, including being able to sue and defend lawsuits.

Fisher claims Robert Zelman deliberately carved out the exception to destroy the Zelmans’ prenuptial agreement. “Martin Zelman is a caring, philanthropic guy,” he said. “He crafted a prenuptial agreement that said to Lois, ‘If I become incapacitated or die, I want you to be protected.’ This is an end-run around the wishes of that guy, who is a good guy.”

Without the right to sue, Martin couldn’t get a divorce, Fisher said. According to the prenuptial agreement, Martin has to file for a divorce himself; it can’t be done by a guardian.

Further, under Florida law, someone declared unfit can’t be divorced for three years. At a hearing earlier this year, Burton pointed out that the little-known law is typically triggered when a competent person tries to divorce someone who suffers from dementia or some other mental illness.

“I honestly never found one case where the person who’s, you know, alleged to be incapacitated is the petitioner in the divorce case,” Burton said. “You know, it’s always the other way around. The petitioner’s the healthy one.”

That’s because, in part, the law is designed to prevent able-minded people from dumping infirmed spouses who would have no ability to defend themselves.

If Martin can’t get a divorce, under the terms of the prenuptial agreement, Lois would be able to continue to live in the couple’s homes in Palm Beach and New York City, keep the couple’s cars, artwork and club memberships and have access to a sizable chunk of her husband’s money — assets Fisher estimated are worth $10 million.

Robert Zelman, who lives in New York City, insists he didn’t know the terms of the prenuptial agreement when he asked that his father be declared incapacitated and that he and one of his sisters, who lives in Oyster Bay Cove, N.Y. be appointed his guardians. His other sister lives in California.

He said he only became involved when his father told him how miserable he was living with Lois, and caretakers expressed concern over how Lois was treating him. “I had no idea if they get divorced she gets nothing,” Zelman said. “This would never have happened if the abuse in the home, we learned about through the statements of the caregivers, had never happened.”

Lois countered that one caregiver trumped up stories after she fired her and another attendant changed his story on the day of a key hearing before Lewis. Further, she pointed out, her husband’s doctor, their rabbi and their longtime friends, including Century Village founder H. Irwin Levy, all testified to their loving relationship.

The night before the hearing that spurred Lewis to kick her out of the condo, she and her husband were out dancing at a party, hosted by Levy. Since then, she hasn’t been able to see her husband. When he saw her in court, she said, he didn’t recognize her.

He now lives with caregivers. “They have isolated him. It’s horrible,” she said. “This is how he is going to end his life? This is justice?”

While she spends some time at a house she owns in Westchester County, N.Y., she spends most of her days in Palm Beach. “It’s a mess,” she said. “What makes it so sad is they broke up a love affair.”

But, Robert countered, since Lois was forced to move out, his father’s health has improved. “I think she overplayed her hand,” he said. “She agitated him so much.”

Further, he said, while Fisher complains that the children stole $3 million from a joint bank account, canceled her health insurance, cut off her memberships at Mar-A-Lago and the Palm Beach Country Club and meted out other financial punishment, Lois has plenty of money. “She’s been travelling the world,” he said, referring to trips she has taken to Jerusalem to be feted by the Israel Museum for her and her husband’s longtime generosity.

Burton will have to sort out the dueling views in June. One of his first orders of business will be determining whether Martin Zelman understands what he is doing and truly wants a divorce. While he can’t overrule Lewis, he can find that Martin is an incompetent witness and therefore can’t be divorced.

“Everybody’s accusing everybody of manipulating this guy. And my question is: If he’s so competent, how come he’s so easily manipulated,” Burton said at a recent hearing. “The question is, does he have a clue to what is going.”