“Gun-free zones” did not always exist. For many young Americans growing up as recently as the early 1960s (Baby Boomers), guns were culturally accepted as part of everyday life. Many eleven-year-old boys went to school with knives in their pockets. A pocketknife was part of being a boy. It was often a gift from their parents. It was a privilege to carry a knife and you didn’t abuse the privilege or you would miss out on the bigger privilege of carrying a hunting rifle. Thirteen-year-old boys in Houston, Texas, used .22 rifles to plink snakes, bullfrogs, and turtles. Seventeen-year-old boys in Syracuse, New York, kept shotguns in their cars at school and hunted game birds like grouse after class. Seventh graders growing up in suburban Los Angeles didn’t have as many opportunities to use guns but they weren’t afraid of guns; those who wanted to shoot would go to a range or their parents would bring them to a ranch in the desert and let them loose with .22 rifles to shoot at rabbits and quail. Farm kids drove around with unloaded guns openly mounted on their trucks and another gun behind the seat. High school shop teachers let students make “projects” like metal handguns and gun cases and boys would bring their rifles in to class for “show-and-tell.”

Across America, boys participated in high school army ROTC, where they shot .22 rifles at ranges connected to their school campus. College students—from Massachusetts to Minnesota—kept cased shotguns in their dorm rooms and used them for hunting on the weekends.

The cultural default was not to assume that people were criminals. The default was to assume that people were innocent until proven guilty. As a result, people had more freedom and more fun, and there was less mass public violence.

***

In the 1920s and early 1930s, mass shootings occurred. But the typical shooter was a hopeless farmer, struggling to provide for his family, who concluded that it would be better for his children to enter eternal paradise prematurely than endure a slow death of starvation. These shooters were different from modern mass shooters in three respects. First, they did not shoot randomly, at strangers in public. Second, their depression stemmed from a sense of helplessness in a dire economy, not schizophrenia or a desire for revenge against social bullies or terrorism. Third, they sought to relieve innocent people of the pain of starvation, not inflict pain.

When JFK was shot in 1963, the nation mourned. Many Baby Boomers, who were schoolchildren at the time, still remember where they were when they heard the news.

One recalls: “I remember it clearly. I was five years old. We were watching the parade on TV and I saw JFK fall over. At first I didn’t realize he was shot, but my grandma screamed. She grabbed her Rosary, made the sign of the cross and began praying. I started to cry. My mom was in the kitchen washing the dishes and she came in and started crying.” She paused for a moment, then added: “We never knew that he was the playboy that he was. We only knew that he was our first Catholic president and that was a pretty big deal.”

Americans wanted to do something to prevent a repeat of such a shocking tragedy.

But three years later, in the summer of 1966, the nation shook again with two mass killings. In July, a hardened criminal and alcoholic named Richard Speck with twenty arrests to his name broke into a Chicago townhouse for nursing students with a knife and a gun. He used the gun to force eight young women into submission. One by one, he garroted the women and used his knife to stop their hearts. In August, a twenty-five-year-old student named Charles Whitman climbed atop a 307-foot tower on the University of Texas at Austin campus and spent eighty minutes randomly spraying bullets, killing sixteen and wounding thirty-one. Whitman had a brain tumor. Modern gun experts attribute the post-1966 acceleration in mass shootings, in part, to the “erosion of community in America.”

After these tragedies, more Americans became open to gun control. Even so, they proceeded with caution because, before JFK’s assignation, there had been only one major public mass shooting on record in U.S. history according to the Washington Post—despite guns being widely available with few restrictions. The 1960s were not that long ago, but our young people have no firsthand memory of this era, where everyone used more common sense. The Democrats of the sixties were nothing like Senator Dianne Feinstein, who told 60 Minutes: “If I could have gotten 51 votes in the Senate of the United States for an outright ban [on semi-automatic firearms], picking up every one of them—Mr. and Mrs. America turn ’em all in—I would have done it!”

Three years after Kennedy’s assassination, in 1966, an influential Democrat, Senate majority whip Russell B. Long of Louisiana told the Associated Press: “I have yet to see a gun control bill which would have prevented the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the killing of the nurses in Chicago or the sniping murders in Texas. These bills might make it more difficult for the murderers to get guns but the man who intends to kill can always get a gun. No matter what we do.”

***

Fast-forward to 1990. Barack Obama is a young man and George H. W. Bush is president. Bush signed a bad bill that included the Gun Free Zones Act of 1990, which made it a federal crime to carry a firearm within one thousand feet of a school—public, private, or parochial. In 1995, the U.S. Supreme Court declared this law unconstitutional, as a violation of the commerce clause, and it went away. Two days after the Supreme Court’s decision, now-president Clinton insisted on bringing the law back. Clinton wanted gun-free zones despite admitting that twice the number of high school students carried guns during the three years of the law’s existence, from 1990 to 1993.

This was not about keeping kids safe. This was about Clinton appearing to keep kids safe so he could get reelected.

Clinton asked his attorney general, Janet Reno, to analyze the Supreme Court’s decision and give him a way “to recommend a legislative solution to the problem identified by that decision.” Reno sat down at her desk and got straight to work.

What Billy wants, Billy gets.

Reno gave Clinton the Gun-Free School Zones Amendments Act of 1995. At Clinton’s request, the Democrat-controlled Congress passed this new gun-free zone regulation. It was a beautifully written law, all about saving the children, while assisting its goal of helping Clinton win a second term. Picture a gorgeous ballerina making syntactical pirouettes through the Constitution and a grand jeté over common sense.

Schools are not the only places that became gun-free zones in the nineties. So did military bases. Bush Forty-One and Clinton share blame for this.

Twenty years later, Obama became president. By this point, Obama knew the history and the stats about gun-free zones and gun control. He should have known that these measures backfire by leaving young people vulnerable to violence—both in the United States and around the world. For refusing to acknowledge those truths, Obama deserves far more blame than the politicians who passed the first gun control measures.

It will take a long time to clean the metaphorical blood that stains Obama’s hands.

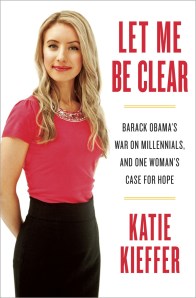

Order “Let Me Be Clear“

Reprinted from the book Let Me Be Clear: Barack Obama’s War on Millennials, and One Woman’s Case for Hope, by Katie Kieffer. Copyright 2014 by Katie Kieffer. Published by Crown Forum, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company.