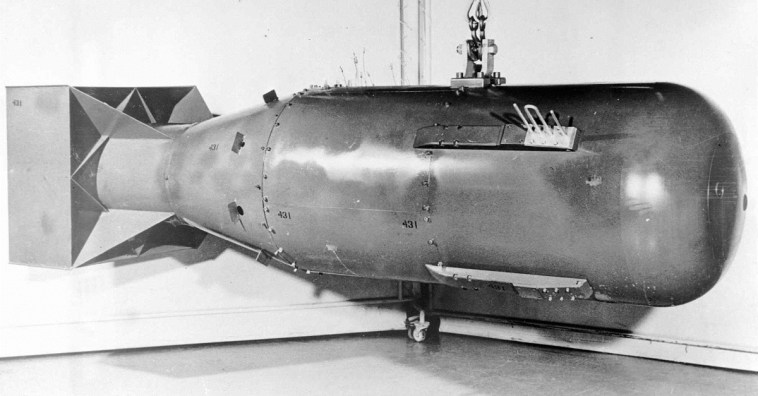

69 years ago, the Enola Gay and the Bockscar hovered above the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to unleash the first atom bombs used in the history of warfare.

Videos By Rare

President Harry Truman’s order to execute the Manhattan Project has been critiqued and questioned ever since and, as a recent San Jose Mercury News article shows, many prominent conservatives of that era were opposed to using the atom bomb and the indiscriminate killing of innocent civilians.

Anywhere from 126,000 to 246,000-plus were killed.

Some of these critics were especially concerned because they felt Japan would have surrendered in a short while anyway.

Here are the words and thoughts of seven prominent conservatives on the atomic bombings of Japan:

President Herbert Hoover

“The use of the atomic bomb, with its indiscriminate killing of women and children, revolts my soul. The only difference between this and the use of gas is the fear of retaliation.” — Written to Army and Navy Journal publisher Colonel John Callan O’Laughlin after the Hiroshima bombing

Dwight D. Eisenhower

“During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.

It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face’. The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude…” — As it appeared in his book, Mandate for Change

Gen. Dwight Eisenhower said to Newsweek in 1963, “the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.”

Adm. William Leahy

“It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.

The lethal possibilities of atomic warfare in the future are frightening. My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.” — As he wrote in his memoir, I Was There

Gen. Douglas MacArthur

“I told MacArthur of my memorandum of mid-May 1945 to Truman, that peace could be had with Japan by which our major objectives would be accomplished. MacArthur said that was correct and that we would have avoided all of the losses, the Atomic bomb, and the entry of Russia into Manchuria.” — A Diary Entry of Herbert Hoover’s

Henry Luce, Time-Life-Fortune publisher

In 1948, the rightward-leaning Time-Life-Fortune publisher Henry Luce told an international Protestant meeting that “unconditional surrender” had violated St. Thomas’ just-war doctrine, and that softer surrender terms in 1945 could have ended the war without the atomic bombing, which “so jarred the Christian conscience.” — From Barton J. Bernstein’s article, “American conservatives are the forgotten critics of the atomic bombing of Japan”

Felix Morley, columnist

An excerpt from Antiwar.com:

[Morley] saw attempts to justify the atomic bombing of Japan – in our day ritually defended by “conservatives” every August like clockwork – as “the miserable farce put on by those who try to reconcile mass murder of ‘enemy children’ with lip service to the doctrine that God created all men in his image.” The atomic bomb was appropriate to a totalitarian order with no fixed moral standards. In Thomistic terms it was “the return to nothingness.”

Morley founded the conservative publication Human Events.

Under Secretary of State Joseph Grew

“[I]n the light of available evidence I myself and others felt that if such a categorical statement about the [retention of the] dynasty had been issued in May, 1945, the surrender-minded elements in the [Japanese] Government might well have been afforded by such a statement a valid reason and the necessary strength to come to an early clear-cut decision.

If surrender could have been brought about in May, 1945, or even in June or July, before the entrance of Soviet Russia into the [Pacific] war and the use of the atomic bomb, the world would have been the gainer.” — An excerpt from Barton Bernstein’s book The Atomic Bomb

Washington Examiner columnist Tim Carney wrote in 2013, “I don’t think Truman’s decision was motivated by evil. I’ll even add that it was an understandable decision. But I think it was the wrong one.”

Carney would write in a separate article, “I’m no historian, and if anyone can refute the facts in this piece, please do — because the article seems to make the clear argument that the atomic bomb was inexcusable.”

The piece he was referring to made a the compelling case that “Japanese leaders, both military and civilian, including the Emperor, were willing to surrender in May of 1945 if the Emperor could remain in place and not be subjected to a war crimes trial after the war … [a] fact [that] became known to President Truman as early as May of 1945.”

If accurate, Truman knew three months in advance that the bombing wasn’t necessary, but gave the go-ahead on the last resort of all resorts anyway.

A decision that obviously haunted some of the right-leaning politicians, journalists and military leaders of that era.

(Photos are from the Associated Press unless otherwise specified)