New York Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a pro-choice Democrat, shocked some of his liberal colleagues when he said he would vote to ban partial-birth abortion. In 1996, he described the gruesome practice as “too close to infanticide.”

Videos By Rare

Paul Cellucci, then the pro-choice Republican governor of Massachusetts, agreed. “That proced-jah,” he said in his Boston accent, “goes too fahhh.”

By the end of the 1990s, that was considered the common-sense position. Regardless of their views on abortion in general, most people did not think a baby—or fetus, if you prefer—should be partially delivered and then killed.

Common sense may be common, but it is not universal. At the height partial-birth abortion debate, I was at an event with a moderate Republican trustee of my college. He suggested the party should abandon its pro-life position. To counter this view, I brought up partial-birth abortion.

“Oh,” he sneered. “Are you partially born again?”

Former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop

was an outspoken opponent of partial birth

abortion.

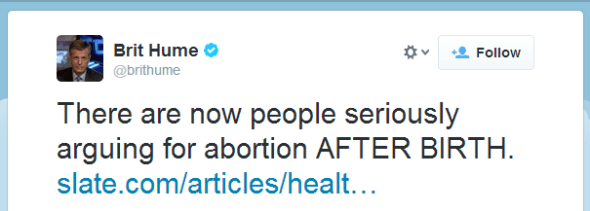

A federal ban on partial-birth abortion passed Congress and was signed by the president over a decade ago. But common sense is still not universal and some want to edge even closer to infanticide.

The philosophers Alberto Giubilini and Francesca Minerva proposed “after-birth abortion” in an article for the Journal of Medical Ethics. This is a term they coined themselves, not one imposed on them by pro-lifers.

Indeed, their title is “After-birth abortion: why should the baby live?”

Their answer, we find out soon enough, is that in their opinion the baby often should not live.

Giubilini and Minerva maintain that conditions that in their view justify abortion frequently obtain after birth as well. So does the dependent state of the child. Under these circumstances, the child could still be terminated.

“[W]e propose to call this practice ‘after-birth abortion’, rather than ‘infanticide,’ to emphasize that the moral status of the individual killed is comparable with that of a fetus … rather than to that of a child,” the philosophers continue. “Therefore, we claim that killing a newborn could be ethically permissible in all the circumstances where abortion would be.”

Nor would this license be confined to ill or severely disabled newborns. “Such circumstances include cases where the newborn has the potential to have an (at least) acceptable life, but the well-being of the family is at risk,” Minevera and Giubilini write.

You may note that we are no longer talking about something close to infanticide, but rather something that is infanticide. Pro-choice Slate writer William Saletan—I reviewed his 2003 book arguing pro-choice conservatives won the abortion wars at the time—says abortion rights supporters should take up the challenge of explaining “why, if abortion is permissible, infanticide isn’t.”

That’s because, he argues, “it isn’t pro-lifers who should worry about the Giubilini-Minerva proposal. It’s pro-choicers.”

Saletan deserves credit for acknowledging many perfectly mainstream pro-choice arguments make this explanation difficult. Pro-choice activists often dismiss the moral significance of fetuses and their development on grounds that could just as easily apply to infants. When they are not denying their humanity altogether, they are describing unborn children as non-persons. (The concept of the human non-person has led to some predictably awful consequences in the past.)

“Abortions at an early stage are the best option, for both psychological and physical reasons,” Giubilini and Minerva write, but not because of any moral claims the developing “non-person” has on us. “Merely being human is not in itself a reason for ascribing someone a right to life,” they add. “Indeed, many humans are not considered subjects of a right to life.”

“If the neurally unformed fetus has no moral claims,” Saletan asks, “why isn’t the same true of the neurally unformed newborn?” The newborn is not fully sentient and from this perspective has as little lose with the taking of her life as a fetus. So why not kill her if she will cost too much money, or interfere with her parents’ life plans, or if she turns out to have some condition that, if detected by prenatal testing, would have led to her abortion?

Maybe there needs to be no reason at all. Our philosophers write, “Indeed, however weak the interests of actual people can be, they will always trump the alleged interest of potential people to become actual ones, because this latter interest amounts to zero.”

There are those who will find such logic revolting when applied to an infant, but totally acceptable weeks, hours or even moments before passing through the birth canal. Indeed, Saletan quotes Ann Furedi, chief executive of the British Pregnancy Advisory Service, as saying, “There is nothing magical about passing through the birth canal that transforms it from a fetus into a person.”

She’s right—but that doesn’t mean what she thinks it means.

In his 2006 pro-life book Party of Death (which I also reviewed at the time, but alas the review is not available online), Ramesh Ponnuru pointed out that academic advocacy for infanticide, often using pro-abortion terminology, was nothing new. Peter Singer and Joseph Fletcher are two of the better known proponents.

“Yet what is perhaps most terrible about these apologias for child-murder is that they have a point,” Ponnuru wrote. “They are not correct about the justifiability of infanticide; but they are correct that if abortion is justified, so is infanticide.”

The only compelling distinction between abortion and infanticide, and it is an important one, is that in the latter case, the woman’s body is no longer involved. But with medical advances slowly making fetal viability occur earlier in pregnancy, even that has its limits. In some cases, premature babies are being delivered that are not developmentally much different than unborn children subject to abortion.

In the movie Knocked Up, the pregnant main character is advised to emulate her stepsister’s abortion. “She had the same situation as you, and she had it taken care of,” her mother says. “And you know what? Now she has a real baby.”

We live in a tough world with a lot of hard cases. But the idea that the same being is a baby when it’s wanted and a blob of cells when it’s unwanted is not sustainable.