CHICAGO (AP) — He has never been elected to anything, not even “student council in high school,” as he boasts. He has little patience for schmoozing. In dealing with people, he admits to being “pretty blunt” – more suited to running a large private equity firm, which Bruce Rauner did successfully for 30 years, than seeking votes for governor, which he intends to do in Illinois next year.

But the traits that might once have made Rauner a bust in politics are beginning to look like possible assets for a Republican in Illinois and for underdogs elsewhere across the increasingly polarized American political landscape. With three quarters of the states now dominated by one party or the other — the highest ratio in recent history — candidates from the other side often seem to have little chance on election day. In this environment, a handful of outsiders are gambling that the time is ripe for challengers who can break out of normal party mold.

Instead of political skills or experience, they have chutzpah – and a lot of money.

“I come from business. I don’t come from the political world, so I call it as I see it. And I think we need a lot more of that down in Springfield,” Rauner, a Republican, declared to an audience of businessmen in overwhelmingly Democratic Illinois. “I can’t be bribed. I can’t be intimidated.”

Rauner, a tall, big-voiced executive who’s worth close to $1 billion, is the star of a class of wealthy Republicans who take inspiration from Gov. Rick Snyder of Michigan and Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, who left the business world in 2010 to beat established Democrats in Democratic strongholds. While technically Republicans, they ran as problem-solving CEOs.

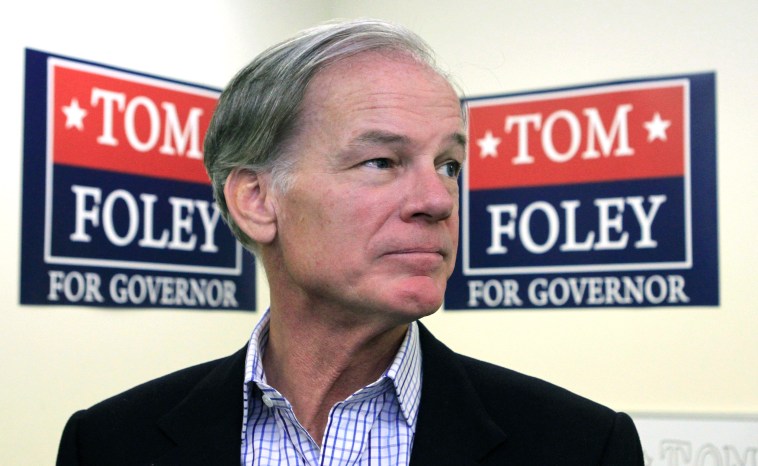

Tom Foley, a former venture capitalist, is expected to run as a Republican for governor of Connecticut. After losing by less than a percentage point in 2010, he hopes to take advantage of Democrat Dan Malloy’s low approval ratings this time. Scott Honour, who made his fortune in private equity and investment banking, plans to challenge Democratic Gov. Mark Dayton in solidly Democratic Minnesota. And Charlie Baker, former chief executive of a hospital group, is running for governor in Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party is shopping for its own business stars or mold-busters to run in Midwestern states where Republicans have taken firm control.

The model is Mark Warner, a cell-phone tycoon who took the governorship away from the GOP in Virginia in 2001. In Wisconsin, they have their eye on Mary Burke, a former executive at the company her father founded, Trek Bicycles, to challenge Republican Gov. Scott Walker.

In addition to the success stories that prominent entrepreneurs tell, they can ante up resources that other first-timers can’t.

“The ability to do that is certainly something we look for,” said Danny Kanner, spokesman for the Democratic Governors Association.

It’s still tough to buck the dominant party trend. In Democratic-leaning California, Republican Meg Whitman, who built a fortune as CEO of eBay, resoundingly lost the 2010 governor’s race despite spending $140 million of her own money.

For the first time since 1952, the one party holds the governor’s office and both houses of the legislature in 37 states; Democrats command the Northeast and West Coast and Republicans the South and Midwest. For outside challengers, the goal is to run as something other than standard bearer of the party in eclipse. Successful businessmen poll well with independent voters and can project an expertise in economics, which is especially attractive in states with battered public finances and high unemployment.

“Now, many of these folks turn out to be lousy candidates,” said veteran national Republican strategist Charlie Black, adding, “but the ones with good political instincts and money have a leg up on the competition.”

A native of Chicago with degrees from Dartmouth and Harvard, Rauner, 56, began campaigning a year and a half before election day, signing up top-tier consultants, running TV and radio ads and making appearances around the state.

For a meeting with businessmen in rural southern Illinois, the 6-foot-4 Rauner rolled up in his Harley Davidson Ultra Classic. His strong baritone made a microphone unnecessary as he delivered his stump speech in a series of bullet-points, much like a boardroom presentation.

“Unacceptable. Outrageous,” he said, closing his assessment of Illinois schools.

He emphasizes his business background — and his lack of political resume. In his field, “the measure of success is wealth creation for shareholders. And when you create wealth for shareholders, jobs get created and economic growth ensues,” he said in an interview.

For a candidate seeking support, he comes on strong and can sometimes give offense.

“Have you met him? Did you get to talk?” former Republican Gov. Jim Edgar asked sardonically. Edgar has — and didn’t.

Democrats have dominated Illinois for the past decade despite corruption scandals. The past three Republican nominees for governor were GOP establishment figures.

Some voters seem intrigued by a different GOP option.

“The status quo obviously isn’t working,” said Laura Donahue, a Republican who met Rauner in Quincy.

In the Republican field, Rauner will face former state Rep. Bill Brady, state Sen. Kirk Dillard and state Treasurer Dan Rutherford. Democratic Gov. Pat Quinn is expected to run for re-election, challenged by former White House Chief of Staff William Daley.

A major issue will be the state pension system, which is $100 billion in debt, and a state bond rating that is the nation’s worst.

Can a rich businessman sell himself as a solution, even to Democratic voters.

Republican professionals are withholding judgment.

Voters “need to know, connect and like Bruce as a candidate,” said Lisa Wagner, an influential Chicago-area fundraiser. “Otherwise, he is just another millionaire running for office.”

—————————————————————————————-

Sara Burnett contributed from Chicago.

Follow Beaumont on Twitter at https://twitter.com/TomBeaumont

Videos By Rare

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.