On Wednesday the Obama White House dumped 100 pages of emails related to the Benghazi cover-up scandal. Even this cherry-picked selection of documents cast serious doubts on the official White House story line. The universal conclusion among commentators was that the emails, intended to stem the crisis, raised more questions than they answered.

Videos By Rare

One critical question is the crisis decision-making timeline. What did senior officials know and when did they know it? Who met with whom, and when? Who made the call to stand down military assets that might have intervened? When did the coverup begin? And where was the president all this time and what was he doing?

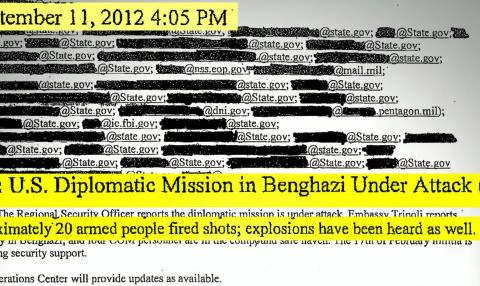

Sadly the dumped emails do not help because the first of them was time-stamped 67 hours after the Benghazi attacks began. This 67 hour gap makes the 18 and a half minute gap in the Nixon tapes look like a hiccup.

However, even if the White House decides to dribble out a few of the earlier official emails, the public is unlikely to get the real story. The most important exchanges probably took place over secret, private email networks.

Under the Federal Records Act it is illegal for administration officials to conduct government business over private email. Official acts are supposed to be a matter of the public record. Government emails are subject to Freedom of Information Act requests, subpoenas, and other forms of oversight. Secret, private email channels seek to evade these measures. And in “the most honest and transparent administration in history,” secret email networks are an epidemic.

Recently the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee uncovered that Labor Secretary nominee Thomas Perez used a “personal, non-official e-mail account almost 1,200 times to conduct official [Justice] Department business since [Perez] became the Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division in October 2009.” Rep. Darrell Issa, R-CA, alleged that Perez “committed at least 34 separate violations of the Federal Records Act.” When asked under oath about using private email accounts to conduct official business Perez claimed he “could not recall.” In another example, Jim Messina, Obama’s deputy White House chief of staff in 2009, coordinated a $150 million advertising campaign with drug companies in support of Obamacare through his private AOL account.

Administration officials try to cover their tracks. Former EPA head Lisa Jackson stood up a bogus account under the name “Richard Windsor” – a combination of her dog’s name and the town of East Windsor, N.J., where she used to live – to correspond with environmental activist groups. The EPA said this account was assigned to Jackson for internal communications, which does not explain why she was using a pseudonym, or why she named her dog “Richard.”

The Obama administration also takes steps to ensure that copies of emails are not available for electronic retrieval. In a case involving NASA, the space agency programmed its system to “delete e-mails from the government server when they were opened remotely by employees using a private computer.” Since the emails would then exist only on the local computer on which they were downloaded, they are functionally hidden. If the computer as located, investigators would have to hope that the emails have not been deleted, the backups not erased, and the hard drive not reformatted – as Obama’s former Environmental Tsarina Carol Browner did while a member of the Clinton administration, hours after a Federal judge ordered all EPA email records to be preserved.

These secret back channels create significant security issues. Keeping sensitive high-level information in the public cloud is criminally foolish. China has been accused of targeting the private Gmail accounts of White House officials,a nd if this is true, Beijing may know more about the Benghazi scandal right now than the U.S. Congress ever will. There is also the case of “Guccifer,” a hacker who allegedly broke into private email accounts of several prominent people, such as Colin Powell, members of the Bush family, and Hillary Clinton consigliore Sidney Blumenthal. The Benghazi-related memos lifted from his AOL account seem to indicate that he knew more about what was going on in North Africa in 2012 than the president. Given Mr. Obama’s generally blasé approach to his official duties and “I know nothing” scandal defense, maybe Blumenthal did.

There are ways investigators may penetrate the secret email network. Jonathan Silver, the former head of the troubled Energy Department $38 billion clean-energy loan guarantee program, issued a memo cautioning staffers to keep a firewall between their private and government email accounts to avoid future subpoenas. (The $500 million in loans for now-bankrupt Solyndra were coordinated on 14 private e-mail accounts.) If a private email address pops up in an official document, it is fair game. Somewhere on a government server or office computer there is an email chain carelessly forwarded to an official account that contains all the secret addresses and phony names of the major players in the Benghazi scandal. It will be the Rosetta Stone to decode all the official business being conducted illicitly outside the purview of FOIA and Congressional oversight. And using it, investigators may be able to begin to fill the 67 hour gap.

James S. Robbins is Deputy Editor of Rare. Follow him on Twitter at @James_Robbins