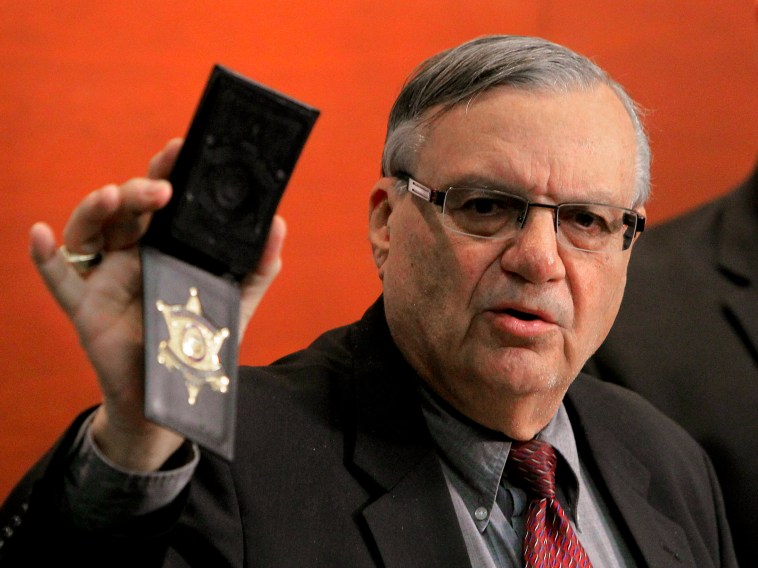

PHOENIX (AP) — Volunteers set up a table outside a music festival one day last month to gather signatures for a drive to oust the notoriously polarizing sheriff of metropolitan Phoenix. The venue, with its largely liberal crowd, seemed the perfect place to drum up support.

Videos By Rare

But it didn’t take long for fans of Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio to show up and deliver a heckling. “Free handouts for illegal immigrants,” one of the sheriff’s backers intoned as other sign-carrying supporters raised their voices to try and drown out those of Arpaio’s opponents.

The recall group walked away with only 100 signatures, compared with the 500 gathered in the same spot a day earlier when the sheriff’s supporters weren’t there.

The confrontation underscores the feisty ground campaign being mounted on both sides — but also the increasing difficulty that Arpaio critics face in getting enough signatures to put a recall before voters.

The recall effort began just weeks after the 80-year-old Republican sheriff started his sixth term in January.

Organizers argue Arpaio should be booted because his office has failed to adequately investigate more than 400 sex-crimes cases and has cost the county $25 million in legal settlements over treatment in county jails. Two pending lawsuits also accuse the agency of racial profiling while conducting immigration patrols.

The sheriff, his critics insist, is more focused on getting publicity for himself than protecting the people.

But recall organizers face long odds. They must gather more than 335,000 signatures by May 30, at a time when they’re running short on money, aren’t attracting deep-pocketed donors and are relying on volunteers rather than paid professionals to sign up supporters.

They also are mounting a campaign against a politician who has a base of devoted supporters and emptied $8 million during the last election cycle, nearly 14 times as much as his closest challenger spent. Arpaio warned in one recent fundraising email that he could lose his post if he’s forced into a recall election.

“We will not be intimidated,” said recall campaign manager Lilia Alvarez. “We are doing work that’s legal and constitutional.”

Nevertheless, big-money donors seem disinclined to support the recall effort. David Berman, a senior research fellow at Arizona State University’s Morrison Institute for Public Policy, said some will likely disapprove of a recall so soon after the November general election, making the prospect of ousting Arpaio a long shot.

“I don’t see this attracting a lot of money for the recall people,” Berman said.

The recall group acknowledged a month ago that it was having difficulties raising money and had to rely on a mostly volunteer work force. Organizers also said they haven’t found big donors to help ease their money problems but believe they can reach their goal through smaller contributions. Others noted that big-money donors aren’t likely to contribute to a cause that may never reach the ballot.

“This would be throwing money to get a theoretical race,” said Joshua Spivak, a recall expert and senior fellow at Wagner College in New York. “The key is money. People don’t get on the ballot without money.”

Recall organizers are trying to build on the success of a 2011 recall effort that ousted then-Arizona Senate President Russell Pearce, an Arpaio ally who was the driving force behind the state’s controversial 2010 immigration law. But the scale of the Arpaio recall is more daunting.

Organizers must turn in more than 335,000 valid voter signatures to force an election. That’s more than the 7,700 needed to force the Pearce recall election and the 216,000 required against former Arizona Gov. Evan Mecham, whose 1998 recall election was scheduled but then cancelled after he was convicted on impeachment charges by the state Senate.

Alvarez said her group has collected 170,000 valid signatures and is aiming for a total of 435,000 signatures by the May deadline — 100,000 more than what is required to offset any names that might be deemed invalid.

Arpaio backers, meantime, aren’t taking the effort lightly.

“We are preparing for the worst. And who knows if they have some buddies out there with deep pockets,” said Arpaio campaign manager Chad Willems, pointing out that labor groups contributed $600,000 to an anti-Arpaio group in last year’s election.

Recall organizers said those groups are using their money this year to push for an overhaul of the nation’s immigration policies.

Arpaio declined an interview request about the recall effort. In the past, the sheriff has apologized for the bungled sex-crimes investigations and said his office has moved to clear up the cases and taken steps to prevent a repeat of the problem. He also has vigorously denied allegations in lawsuits by the U.S. Justice Department and a group of Latinos that his deputies racially profiled people in traffic patrols targeting illegal immigrants.

Arpaio allies have mobilized to try to protect the sheriff.

One group filed a still-pending lawsuit that asks a judge to order an end to the recall effort. And Arpaio allies at the Legislature proposed retroactively adding a primary to recall races — a move that would likely have benefited the sheriff — but the measure was defeated last week in the state Senate.

Arpaio’s campaign committee has paid for its own signature-gatherers to circulate a non-binding petition that opposes the recall effort. Willems said the idea was to have the sheriff’s supporters in the same public space as recall organizers to offer an alternative.

That’s exactly what happened outside the music festival in downtown Phoenix on March 23. Frustrated by their lack of success, recall organizers chose a different spot to try and collect signatures the following day: an anti-bullying event.

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press.