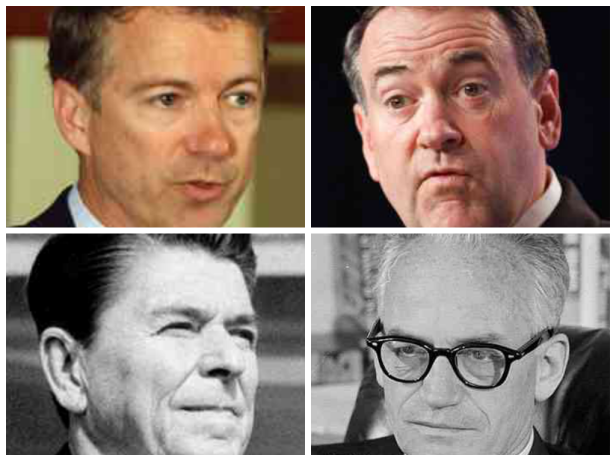

Republican presidential frontrunner Mike Huckabee warns “libertarianism is not Republicanism.” Senator Lindsey Graham has declared, “We are not going to build this party around libertarian ideas.” Former Senator Rick Santorum says, “I fight very strongly against libertarian influence within the Republican Party and the conservative movement.”

Videos by Rare

Conservatives who see rising libertarian influence in the GOP as a problem are not only wrong.

They forget recent history.

Bush-Cheney was one of the least conservative eras in the last half century. Government and the debt exploded at a rate surpassed only by Obama. Medicare Part D was the largest entitlement expansion since LBJ. Bush’s tenure began with doubling the size of the Department of Education and ended with bailing out Wall Street. The Weekly Standard’s Fred Barnes praised Bush as representing a new “Big Government Conservatism” while Dick Cheney insisted “deficits don’t matter.”

There wasn’t even the pretense during Bush-Cheney that government should be smaller. In 2003, The Manchester Union-Leader reported of National Committee Chairman Ed Gillespie, “the party’s new chairman, energetic and full of vigor, said in no uncertain terms that the days of Reaganesque Republican railings against the expansion of federal government are over.”

One could argue that Reagan talked a good small government game, but like Bush, he ultimately expanded the state. Conservatives could also argue, in Reagan’s defense, that Congress never delivered on promised spending cuts.

Regardless, despite any failings, Reagan always fought for and promoted limited government. Bush never did. He never even tried. As columnist James Antle compared them, “Bush’s record on spending was much worse than Reagan’s, and so was his rhetoric. Reagan’s speeches kept conservatives focused on the evils of government growth even when his actions did not.”

Fred Barnes got it right in 2003: “Reagan was a small government conservative who declared in his inauguration address that government was the problem, not the solution. There, Bush begs to differ.”

In addition to rejecting small government philosophy, the issues that unified conservatives most during Bush-Cheney were definitively anti-libertarian: support for the Iraq War, the Patriot Act, warrantless wiretapping and “enhanced interrogation tactics.”

Some of Bush’s foreign policy decisions and national security measures must be viewed through a post 9-11 lens, but still do not justify his ultimate legacy from a conservative perspective: A Republican president explicitly rejected the core tenets of small government and constitutional liberty that had defined American conservatism for essentially its entire history.

Barry Goldwater famously said that “extremism in the defense of liberty” was no vice. Reagan believed conservatism proper was like a three-legged stool consisting of national security, religious and economic-libertarian conservatives.

Barry Goldwater famously said that “extremism in the defense of liberty” was no vice. Reagan believed conservatism proper was like a three-legged stool consisting of national security, religious and economic-libertarian conservatives.

Bush certainly represented national security conservatives. He was popular with religious conservatives.

But during his watch, the libertarian leg of Reagan’s stool was virtually non-existent.

So why, ultimately, did the last Republican administration fail so terribly in advancing conservatism? Because Bush-Cheney represented a Republican Party completely void of libertarian influence.

Those eight years reminded us that where the conservative movement has been the least conservative is also where it has been the least libertarian.

Being libertarian means, first and foremost, holding the ideological position that government is undesirable. Liberals generally hold the ideological position that government is a democratic force for social change and justice, and thus, a positive good. Libertarians—and most conservatives, in most eras—have considered government positively bad: A leveling force that squelches creativity, natural diversity, inhibits the free market and hampers human innovation.

When President Obama or Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid accuse libertarian leaning Republicans of being “the party of no government” or “anarchists,” their accusations are factually ridiculous. But however perverse, they do denote an anti-government libertarian component that had theretofor been lacking in the GOP.

Goldwater and Reagan also emphasized this. Unfortunately, Goldwater’s brand of liberty was too extreme for America in 1964. Even so, as a product of Goldwater and that history, Reagan famously declared in 1975 that libertarianism was the “heart and soul of conservatism.”

One could argue that Goldwater-Reagan conservatism is outdated and in some ways it might be. Different eras call for different policies and ideas. But it is quite another thing to argue that limited government philosophy—the core of historic American conservatism—is outdated. I know very few conservatives who would say this.

If surveying the right’s ideological history, Goldwater’s vision, Reagan’s revolution and Bush’s failure all point to one hard-to-ignore fact for any conscious conservative: It is no doubt possible to be a libertarian without being a conservative. But it is, by definition, impossible to be a conservative without also, to some degree, being a libertarian.

In fact, Reagan’s axiom—that “government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem”—is the eternal libertarian mantra.

Republicans worried about the rising tide of libertarianism in their party, or who think it’s a problem, forget that we already saw their libertarian-less GOP just a few short years ago. It was awful. We should not want to revisit that time again.

Huckabee, Graham, Santorum and others who fear that a more libertarian Republican Party is emerging, complain that this new GOP looks unfamiliar to them. They’re right. But it’s also not anything new.

Questioning whether conservatives should embrace libertarianism has never really been about libertarians.

It’s about whether conservatives intend to be conservative. Again.