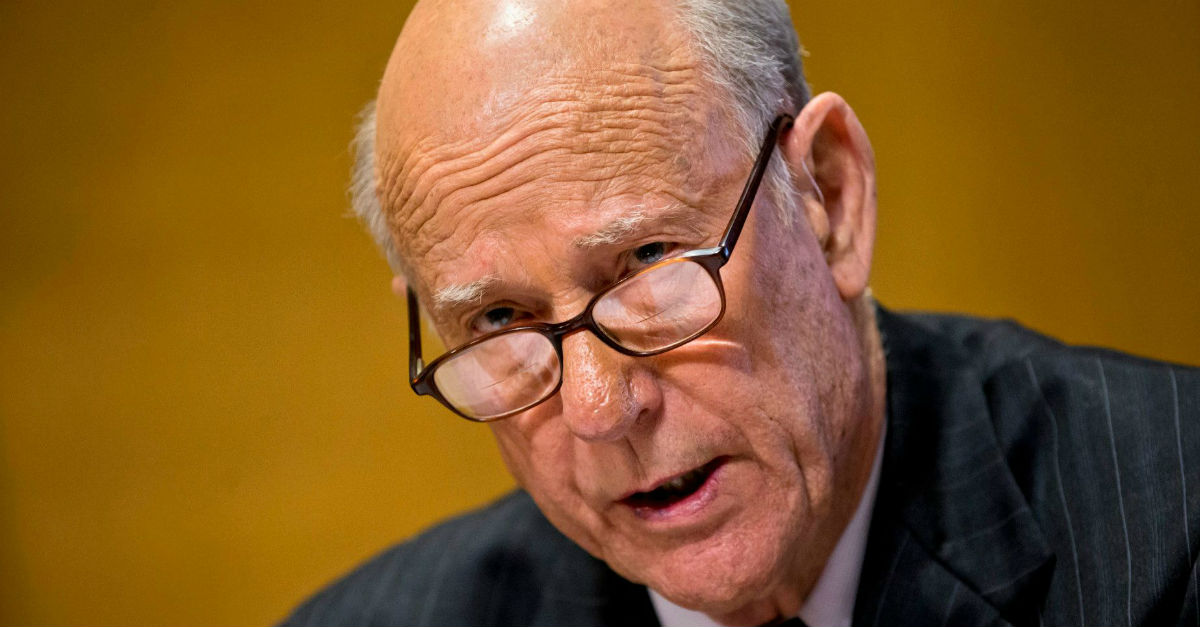

Last night Kansas Senator Pat Roberts won his primary election with 48.1% of the vote, 7.3 points ahead of his nearest rival, tea partier Milton Wolf.

Videos by Rare

Roberts is a shoo-in for re-election, so this would hardly be worth mentioning, except that polls showed Roberts winning the primary by 15 or 20 or even 30 points. Are the polls broken?

Yes and no. There was evidence of a late surge for Wolf, with the polls taken closer to election day showing somewhat tighter margins. And some of the most accurate polls weren’t released publicly at all.

SurveyUSA showed a 33-point margin in June, then a 20-point margin in July. Politico’s Tarini Parti wrote last week that “in the aftermath of House Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s shocking primary defeat, even a 20-point gap isn’t enough to comfort establishment Republicans when the trend line is moving in Wolf’s favor.”

That was a somewhat odd assertion. The polls in Cantor’s race were way off, but that was a House race. It’s more difficult for a pollster to get a good sample in a congressional district than it is in an entire state.

Yet Parti’s reporting was accurate: Her Republican sources really were nervous that the race was tighter than it looked. That wasn’t because of the public polls. It was because her sources had access to more accurate internal polling.

Internal campaign polling presents a paradox: It’s both more reliable and less trustworthy.

What makes internal polls more reliable is that campaigns can spend more money on them. That means they can make more calls, filter likely voters more precisely, rebalance their samples to reflect regional populations, and take other steps that are prohibitively expensive for public pollsters, whose clients (usually media outlets) simply won’t pay what campaigns will.

But what makes internal polls less trustworthy is that they remain private unless campaigns choose to make them public — which a campaign (or party, or political action committee) only does if a particular result serves its candidate’s interests.

That introduces a bias that makes internal polls that are released publicly consistently less accurate than public polls.

In the case of Kansas, the only poll showing the race within single digits was touted in a fundraising letter by the Senate Conservatives Fund, which backed Wolf.

That poll happened to be accurate, but it never would have seen the light of day if it had looked better for Roberts.

In other words, internal polling is only trustworthy if you’re seeing all of a campaign’s internal polls, which you aren’t seeing unless you actually work for the campaign.

The next-best thing to actually seeing a complete picture of the internal polling is having candid conversations with people who do. That’s one reason why, even as election coverage has been improved over the last decade by the increasing prominence of polling analysts and political scientists, well-sourced campaign reporters remain invaluable.