Lou Gehrig — the name has surfaced often in recent weeks as many across the nation dump buckets of ice over their heads to raise money and promote awareness of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), otherwise known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Videos by Rare

The neurodegenerative disease was discovered first by the French pathologist Jean-Marie Charcot in the nineteenth century. It is a disease for which there is still no cure.

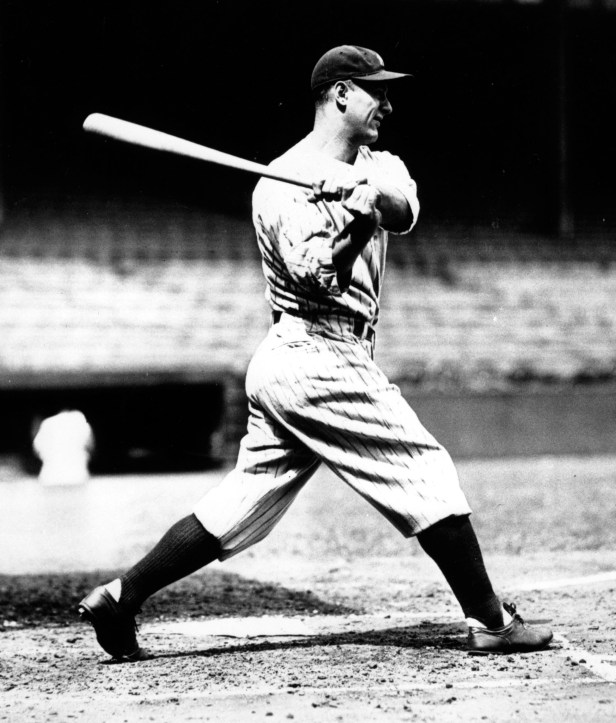

In almost the blink of an eye–a perennial all-star, two-time MVP, six-time World Series winner, the man that batted behind Babe Ruth, the man who was dubbed the Iron Horse for his durability–just couldn’t swing the bat the way he used to and couldn’t understand why.

In the second half of the 1938 season, only a year removed from a typically excellent campaign, Gehrig began to suffer from exhaustion. “I tired mid-season. I don’t know why, but I just couldn’t get going again,” he remarked at season’s end.

By 1939, Gehrig had played in an astounding 2,130 consecutive games — a record that stood until Cal Ripken Jr. broke it in 1995. Gehrig unexpectedly asked to be scratched from the lineup card on May 2.

He would never play another game.

Gehrig was a shoo-in hall of famer the moment he stepped across the first base line for the last time, but his journey was only beginning.

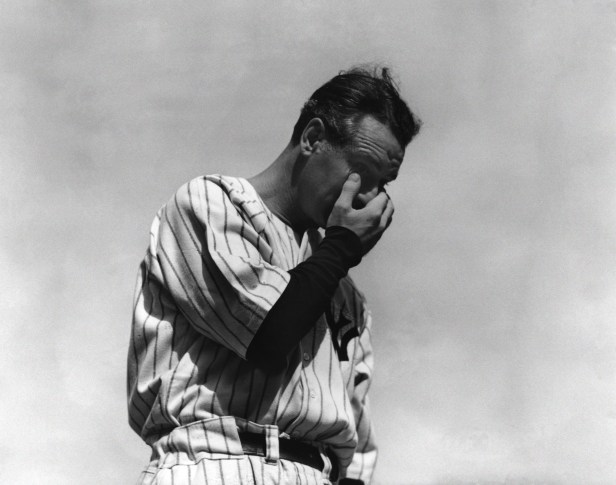

The Iron Horse received the bad news on June 19, 1939, his 36th birthday. For his exploits on the baseball diamond, Gehrig was and was destined to remain a household name. But it was the courage in the face of terminal illness, courage on full display in his parting speech to Yankees fans — the stuff Hollywood wishes it could write — that told us about Lou Gehrig the man.

Though his body had slowed at a steady rate and his future in peril, he considered himself the “luckiest man on the face of the earth” and even faced his own mortality with good cheer.

His speech:

Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about the bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. I have been in ballparks for 17 years and have never received anything but kindness and encouragement from you fans.

Look at these grand men. Which of you wouldn’t consider it the highlight of his career just to associate with them for even one day? Sure, I’m lucky. Who wouldn’t consider it an honor to have known Jacob Ruppert? Also, the builder of baseball’s greatest empire, Ed Barrow? To have spent six years with that wonderful little fellow, Miller Huggins? Then to have spent the next nine years with that outstanding leader, that smart student of psychology, the best manager in baseball today, Joe McCarthy? Sure, I’m lucky.

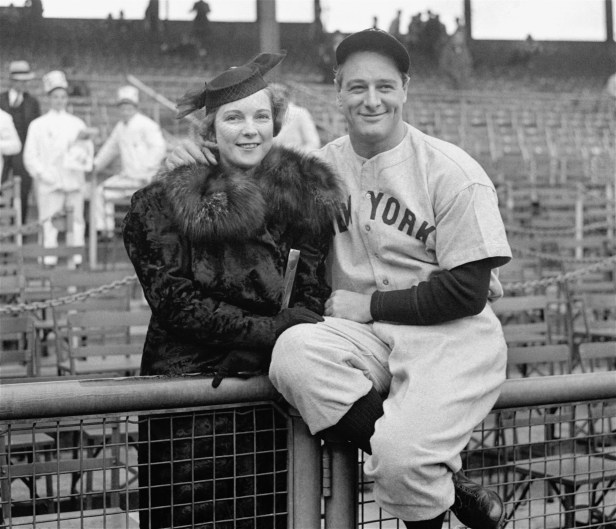

When the New York Giants, a team you would give your right arm to beat, and vice versa, sends you a gift — that’s something. When everybody down to the groundskeepers and those boys in white coats remember you with trophies — that’s something. When you have a wonderful mother-in-law who takes sides with you in squabbles with her own daughter — that’s something. When you have a father and a mother who work all their lives so you can have an education and build your body — it’s a blessing. When you have a wife who has been a tower of strength and shown more courage than you dreamed existed — that’s the finest I know.

So I close in saying that I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.

On July Fourth, of all days, Gehrig delivered the speech that guaranteed his place in the annals of American lore, where he will reside permanently. There’s a reason his speech has been referred to as “Baseball’s Gettysburg Address” and there’s a reason Gary Cooper won an Oscar when he played Gehrig in Pride of the Yankees. Gehrig’s achievement was likened to a landmark speech, memorized and recited by a Hollywood A-lister for all of America only a year after ALS had won the battle.

Gehrig died on June 2, 1941 and was survived by his wife Eleanor.

Baseball has charms that other American sports do not have. It is the oldest and the first major sport played in America; it brings us closer to America’s roots and founding than any other sport.

The historian Jacques Barzun once said that “whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.” The poet Walt Whitman, too, loved the game, saying: [I]t’s our game: that’s the chief fact in connection with it: America’s game: has the snap, go fling, of the American atmosphere — belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly, as our constitutions, laws: is just as important in the sum total of our historic life.”

Baseball then taps into what it means to be American — the American Dream — in no small way because it can turn the son of poor German immigrants like Gehrig into a tragic, mythical figure who snaps us back to the broader narrative of American existence.

Robert Benne and Philip Hefner wrote in their book “Defining America: A Christian Critique of the American Dream” that the American Dream “grounds individual or group experience in a reality that transcends their particular experience of existence … in a broader and deeper context.”

If you require evidence that baseball is a uniquely powerful American activity in this way, you needn’t look any further than the Lou Gehrig story. The meteoric rise, the swift fall and the tranquil ride off into the sunset of his life made Gehrig the stuff of myth — made Gehrig an American hero.

Perhaps lost in the matter-of-fact uttering of “Lou Gehrig’s disease” is what Lou Gehrig the person has meant for America. In one sense, ALS was the disease that killed him.

In another sense, it’s made him live forever.

(Photos credit: The Associated Press)