Less than a week after 22-year-old Elliot Rodger’s shooting-stabbing spree that left six victims dead and a dozen injured, we hear familiar calls to “do something” to prevent this from ever happening again.

Videos by Rare

The California state legislature plans to introduce gun restrictions next week. This is a state that has already seen door-to-door gun take backs from thousands of people thought to be too dangerous to have them because of a mental health issue, a felony, or a domestic violence record.

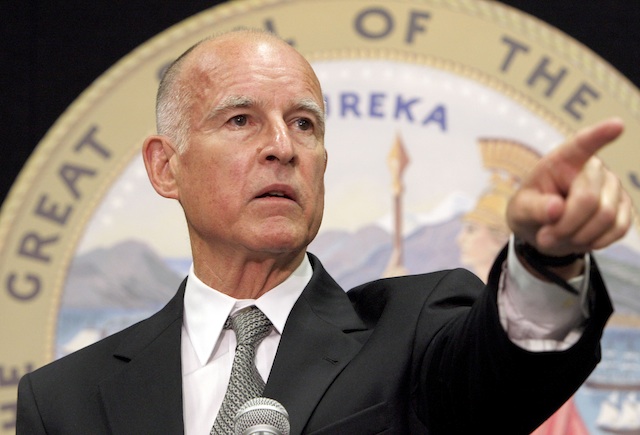

Those folks had purchased the guns legally, but according to Gov. Jerry Brown, they lost those rights. New legislation would allow law enforcement and individuals to petition a judge to temporarily prevent someone deemed dangerous from purchasing a firearm.The New York Times reports, “the process would be similar to the one currently used for restraining orders in cases of domestic violence.”

For all that, the bill might not pass. California’s laws are already some of the toughest in the nation. The state is a lot more than LA and San Francisco — there are large rural, conservative populations after all. And going after the mentally ill is not quite as appealing among folks who might be keen on disarming the angry white boogeyman of Salon’s nightmares.

It’s not just the state government — or the feminists — that are champing at the bit to “do something” to prevent another massacre. Ann Coulter put her oar in, as she did post-Sandy Hook shooting. She helpfully suggests that the blame for this kind of massacre lies squarely with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and probably Thomas Szasz for helping make it harder to have “crazies” committed.

This week, Coulter straw-manned against folks who argue against stigmas against the mentally ill. Certainly Rodger was mentally ill, he had some instance of violence that should have been concerning. But how violent, how weird, how angry does someone have to be before their rights are void? It’s a fair question and one that underlines why the mentally ill have concrete reasons to fear a stigma.

Eighteen percent of Americans have suffered some kind of broadly-defined mental illness. The majority of them — even the majority of the 4 percent who suffer from serious, life-restricting mental illness — do not go on killing sprees or commit any violence at all.

Coulter, in arguing for the increased ability to imprison a man indefinitely for strange behavior or force him at gunpoint to take his meds, is making the case for a violation of fundamental rights bigger even than taking away his Second Amendment ones. In the midst of her anti-left schtick, she fails to notice this time and again. Perhaps some people try very earnestly to get rid of mental illness’ “stigma” not because PC is ever in fashion, but because they are worried about being locked indefinitely into the loony bin.

Coulter expresses blithe confidence in the psychiatric profession in her pieces. One wonders if she feels the same way about New York Times guest editorialist Richard A. Friedman, a professor of clinical psychiatry who writes that the failure of our reaction to the Rodger shooting and other tragedies lines in our belief we can predict and prevent violence. We can’t, and Friedman knows this, but he concludes with a plea for blanket gun control anyway.

A more heartrending response to the shooting is coming from Richard Martinez, who lost his son Christopher to Rodger’s murderous rage. Last weekend, Martinez tearfully ranted to CNN about “craven, irresponsible politicians” who had failed to enact federal gun control after the Sandy Hook shooting.

This is an understandable, incomprehensible rage from a father who just lost his son. But grief does not make good legislation. And hasty legislation in response to a crisis, well, it seems like we should have learned to avoid that by now.

All of these reactions are typical after an act of violence. “Never again” is a great goal, but it doesn’t workwith dictatorships or ethnic violence. It doesn’t apply to shootings either, because freedom and choice and 330 million people in the U.S. and 300 million guns means there will always be bad actors. But these truths do not apply when it’s time to do something — anything! — even when that thing is impossible, unconstitutional, or immoral.

For all the political responses and emotional pleas after a shooting, the most unforgettable comment to me remains another father of another shooting victim. Christina Taylor-Green, age 9, was killed by Jared Loughner in the January, 2011 shooting that gravely injured Rep. Gaby Giffords and killed five in addition to Christina.

Green’s father John in a Fox News interview a few days after the shooting had a voice thick with tears. But he also called the shooting “a random act” and “such a rare thing to happen.” And in spite of his loss, he also managed to say, “If we live in a country like the United States where we are more free than anywhere else, we are subject to things like this happening, and I think that’s the price we have to pay.”

It wasn’t right, or fair, or just, what happened to his daughter, but Green seems to have instinctively known even then what people much further from these tragedies never seem to understand — that in an imperfect and still relatively free country, there may simply be nothing anyone can do to stop these shootings.

That admission doesn’t make any shootings okay. It just means we are accepting at last that we cannot control humans like robots, no matter what legislation we hastily pass. Nor should we try.