The death of Eric Garner — and the graphic video that showed the step by step events leading up to it — sparked an investigation by one newspaper of police killing-indictment statistics in New York City.

Videos by Rare

The findings of the New York Daily News raise some interesting questions.

Over the last 15 years (since 1999), there have been 179 people killed by on-duty NYPD officers and only three of those killings have resulted in indictments. Two of those indictments didn’t result in convictions and the one conviction resulted in no jail time.

In other words, 98 percent of the time juries say no to charges, 2 percent of the time they say yes, .55 percent of the time someone is convicted and 100 percent of the time no one goes to jail.

On top of this, the Daily News reports, “roughly 27 percent of people killed by cops were unarmed.” That’s roughly 48 cases out of 179. In the absence of context or individual information on each incident, the numbers look suspect.

Could it be that police have not been to blame in any of these killings of unarmed people, that the officer acted reasonably or in self-defense proportionally each time?

Perhaps some of these cases fall more into the Michael Brown category — i.e. there was allegedly a struggle for a gun — than the Eric Garner category. Brown technically wasn’t armed, but some testimony suggested he was trying to be. Eric Garner was breaking a law on the level of speeding, yet ended up dead.

The Brown-Wilson, Garner-Pantaleo incidents played out in close proximity and neither yielded indictments. In the Michael Brown case, forensic evidence, eyewitness accounts and Officer Darren Wilson’s word painted a portrait of reasonable response. In the case of the latter, there was a video, there was a petty crime, there was no apparent threat of violence and there were numerous calls for help from Garner: “I can’t breathe.”

It is neither logical nor respectful to condemn the entire jury system or law enforcement based on the Garner case, but important questioning is warranted. Why are police rarely indicted in killings?

There are plenty of killings samples and the results are pretty stark.

According to the New York Times, “41 officers were charged with either murder or manslaughter in shootings while on duty over a seven-year period ending in 2011. Over that same period, police departments reported 2,600 justifiable homicides to the F.B.I.”

That’s a ratio of justified to unjustified killings over that time is roughly 63.4 to 1.

What about the Garner case? Wasn’t the video evidence enough to say: The officer clearly didn’t intend to kill him, but “Oops, sorry about that” doesn’t cut it when someone dies?

The lack of intent in a killing lessens culpability, but it shouldn’t remove culpability entirely. With police killings, it seems lack of intent is more likely to remove culpability — an officer may be legally justified in using deadly force merely because he feels threatened at the time, whether or not a threat existed in reality.

When the public gets loud, the officer may be out of a job.

But is losing one’s job really enough?

But back to juries. Ben Casselman of FiveThirtyEight recently laid out three possible reasons that grand juries decide not indict officers who have killed people in the line of duty.

1) “Jurors tend to trust police officer and believe their decisions to use violence are justified, even when the evidence says otherwise.”

2) “The second is prosecutorial bias: Perhaps prosecutors, who depend on police as they work on criminal cases, tend to present a less compelling case against officers, whether consciously or unconsciously.”

3) “Ordinarily, prosecutors only bring a case if they think they can get an indictment. [I]n high-profile cases such as police shootings, [prosecutors] may feel public pressure to bring charges even if they think they have a weak case.”

Knee-jerk support of police, a conflict of interest or not enough evidence.

The Daily News quoted Robert Gangi, executive director of the Prison Reform Organizing Project, on the second point.

Gangi believes that prosecutor-police relationships presents a conflict of interest that is key in why many cases don’t result in charges.

“In most of those cases it would be the local district attorney who’s bringing up the charges, if any,” he said. “There’s an inherent conflict of interest … The police and DA work very closely together, and so they need each other to carry out their jobs.”

That’s why many people believe special prosecutors should be appointed to deal with these high-profile local issues. Several states have adopted this stance.

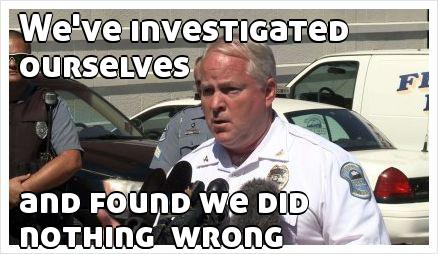

No one wants to see memes like this anymore:

This isn’t all to say that police are never justified when they kill someone–but it is to say that it’s hard to believe they almost always are, particularly when those killed, like Garner, are unarmed.