As many know, the USA Freedom Act will not move forward after Tuesday’s vote in the Senate. This result has been widely hailed as the failure of NSA reform—but that summary of what happened is more convenient than accurate.

Videos by Rare

What actually happened is far more interesting for both partisan politics and the future of the NSA.

First, let’s look at the bill itself

Much ink has been spilled over whether this is a bill civil libertarians should support or oppose, and the answer is complicated.

See, the original incarnation of the USA Freedom Act was quite different from the much-amended version which went to a vote this week. Rep. Justin Amash (R-MI), who helped write that first version but ultimately voted against the final version, explains some of the differences here:

This morning’s bill maintains and codifies a large-scale, unconstitutional domestic spying program. It claims to end “bulk collection” of Americans’ data only in a very technical sense: The bill prohibits the government from, for example, ordering a telephone company to turn over all its call records every day.

But the bill [was] weakened in behind-the-scenes negotiations [… And] while the original version of the Freedom Act allowed Sec. 215 of the Patriot Act to expire in June 2015, this morning’s bill extends the life of that controversial section for more than two years, through 2017.

These are big changes. Writing at Antiwar.com, Justin Raimondo had even harsher words for the final version of the bill. “Rather than fundamentally changing the way the NSA scoops up data, the bill merely outsources collection to immunized telecoms,” he notes, “compelling them to do the NSA’s dirty work.” Raimondo also argues that the Orwellian language and numerous transparency loopholes will allow the surveillance state to codify and even expand its intrusions into our privacy.

So why did this revised version of the USA Freedom Act still get so much support, even from libertarians? Well, the argument is essentially that it’s better than nothing—a “good start,” if you will. Whether the bill truly would have ended nationwide bulk surveillance, brought more transparency to the NSA, and made other reforms detailed by the ACLU here is highly debatable, but at least some improvement was a possibility.

Now, the vote breakdown. Let’s start with the Democrats

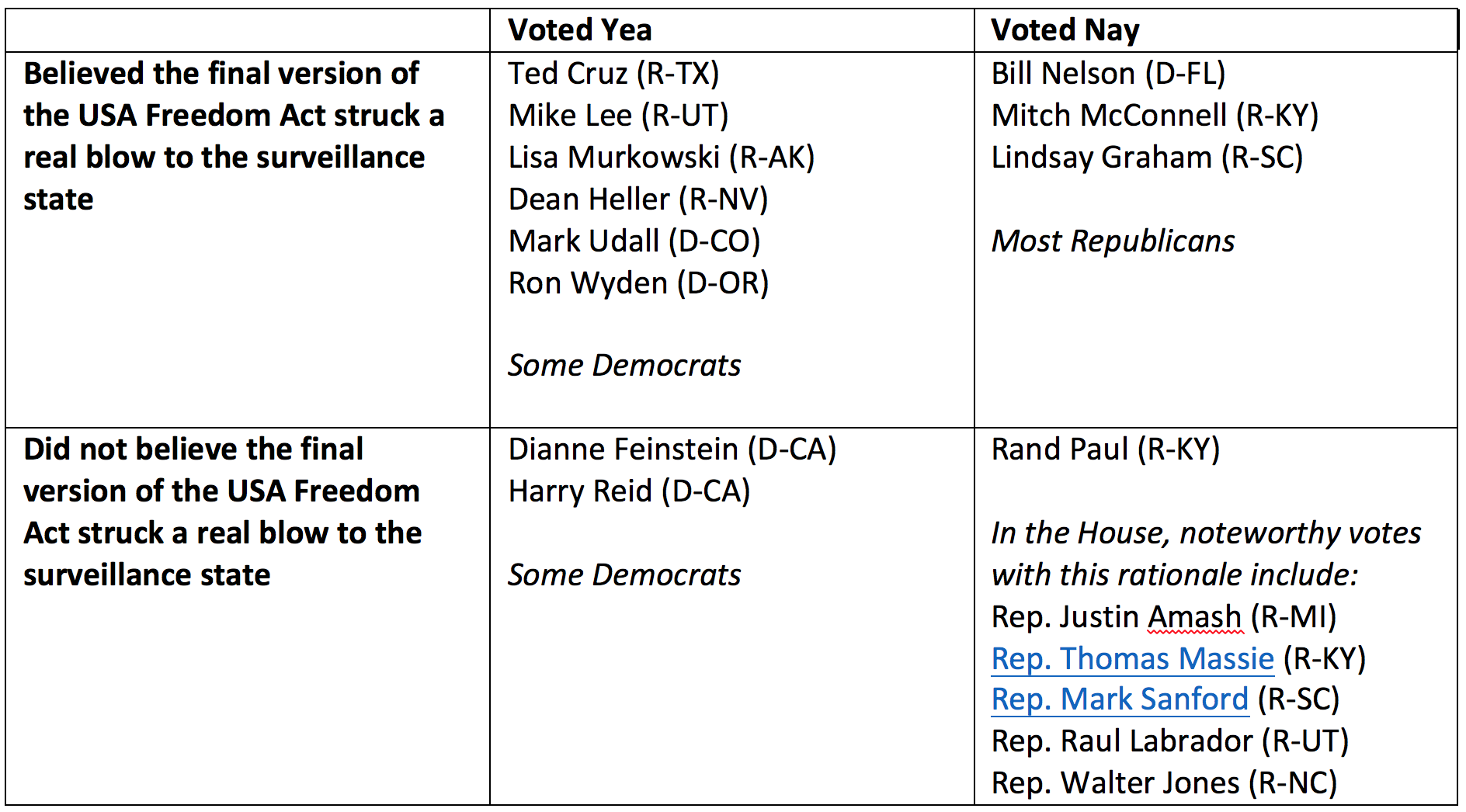

All but one, Bill Nelson (D-FL), voted in favor of the bill. Nelson’s vote was motivated by his concern that the USA Freedom Act would have “undone a provision allowing for retention of certain telephone records that he feels is helpful in preventing future terrorist attacks.” In other words, he voted nay because he didn’t want to weaken the surveillance state.

Then there’s Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA). She voted yes, but with significant reservations. Feinstein—who has been a staunch defender of the NSA despite being hypocritically upset when the CIA spies on her—ultimately supported the bill because she thought it wouldn’t do much to weaken the NSA.

Outgoing Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (N-NV) also supported the bill, arguing that that it was a bipartisan compromise which should please all comers, offering some civil liberties protections while it “continues to give the U.S. intelligence community the ability to gather the information it needs to keep America safe.” (Never mind, of course, that there is exactly zero concrete evidence that NSA spying has kept us safe.)

He also wanted to add elements of SOPA, the internet censorship proposal, to the USA Freedom Act to mutate it even further from its original form. Indeed Reid, like Feinstein, has never been too worried about domestic surveillance, so it seems safe to assume that he too voted for the bill because he thought it wouldn’t do much to weaken the surveillance state.

But not all Senate Democrats are so down on civil liberties. Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Mark Udall (D-CO) in particular have been fierce opponents of the NSA. Wyden and Udall joined Justin Amash earlier this year in decrying the watering down of the USA Freedom Act to its current state—but they both ultimately voted for it. Udall urged his Senate colleagues to continue pressing for stricter reforms, as did Wyden.

Now, let’s talk about the Republicans. The splits here are even more fascinating

Only four Republicans voted in favor of the bill: Ted Cruz (R-TX), Mike Lee (R-UT), Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), and Dean Heller (R-NV). All four have stated their support for limiting the surveillance state, and Cruz and Lee in particular are known as leaders in the tea party movement. Like Udall and Wyden, some of these senators may prefer more powerful NSA reforms, but they decided the USA Freedom Act was a good enough start.

The Republican nay votes were almost uniformly motivated by a desire to keep the surveillance state strong. Incoming Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) exemplified this position, arguing that the bill would be “tying our hands behind our backs” in the fight against terrorism. (Again, recall that there’s no real evidence the NSA keeps us safe.)

Other Republicans were even more virulent in their opposition to any possible reduction of the surveillance state. The perpetually hawkish Sen. Lindsay Graham (R-SC), for instance, said, “I don’t like the bill, I’ve never liked the bill, and I’m going to everything I can to kill this and start over again next year. This bill guts the ability to defend ourselves when we’re very much at risk.”

And then there’s Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY). I said that the GOP nay votes were “almost uniformly motivated” by love of the NSA because Paul is the one exception. He voted against the USA Freedom Act for basically the same reasons Amash provided, albeit with a primary focus on the renewal of the PATRIOT Act. Paul stated that renewing the PATRIOT Act was an amendment he simply could not support, a stance for which he deserves kudos.

To summarize the votes:

Both parties are divided over whether the NSA needs serious reform, but only the GOP has a hardline civil liberties faction which is not content with moderate and dubious changes. That faction’s vote here—which could so easily be maligned by news outlets eager to report a conveniently simple story about this vote—is a promising display of principle by the liberty wing of the Republican Party.This is a remarkable split across party lines—it is, in the words of the bumper sticker, not so much left vs. right as the (surveillance) state vs. us.

Future developments could be more interesting still. While some have suggested that this version of the USA Freedom Act was the best NSA reform bill likely to make it to a vote in the foreseeable future, there is also an argument to be made that this loss paves the way for future, better reform. Passing this weakened bill would have allowed many people, voters and politicians alike, to assume that the NSA issue is “fixed” and need not be addressed again.

Either way, I’d suggest that the weakness of the bill is itself a major reason it didn’t pass—not because the Senate was champing at the bit for stronger civil liberties protections, but because we are. This analysis from The Guardian puts it well:

The USA Freedom Act failed because it was a weak reform bill that didn’t accomplish enough good to excite a grassroots base that would fight for it and ensure victory. […] It only targeted a small portion of the types of surveillance we know the NSA and other agencies are conducting. And it had been so badly watered down since its introduction that, for an internet public whose trust had been violated in the worst way, common sense told people not to trust it.

Enacting real surveillance reform will unquestionably be a hard battle, but settling for half measures is not a viable shortcut. It is tepid opposition to the encroachments of intrusive big government in the name of safety which got us to where we are today, and similarly tepid reform measures are not enough to halt the choking advance of the surveillance state.

That is not to say that there is no place for incremental progress in politics—indeed, Rand Paul is frequently critiqued by libertarians for being too much of an incrementalist. But it is to say that uncertain reforms paired with a certain renewal of the PATRIOT Act is not much of an advance for civil liberties. It’s not even enough of an advance to fire up the internet it ostensibly protects.