Helping another person even when doing so could adversely affect you is considered a virtue by many. People are often applauded as heroes, as they should be, when they help others. But what happens when a well-intended action results in unanticipated harm?

Videos by Rare

Expand that thought one more step: What is the effect if the resulting harm should have been known, but the persons taking action out of supposed “altruism” based their actions on emotions rather than on data? They meant to help, but they ended up hurting someone or some group — either themselves, the intended beneficiary of the action or a third party.

In a paper titled “Concepts and Implications of Altruism Bias and Pathological Altruism” (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, June 4, 2013), Barbara Oakley, associate professor of engineering at Oakland University, lays out arguments that altruism, what we think of as unselfish, helpful behavior, can be pathological. Actions thought to benefit another person or persons can have unreasonable, negative consequences to that person or group and even to the person carrying out the action.

“Pathological altruism,” Oakley writes, “can be conceived as behavior in which attempts to promote the welfare of another, or others, results instead in harm that an external observer would conclude was reasonably foreseeable … an observable behavior or personal tendency in which the explicit or implicit subjective motivation is intentionally to promote the welfare of another, but instead of overall beneficial outcomes the altruism instead has unreasonable (from the relative perspective of an outside observer) negative consequences to the other or even to the self.”

In simpler terms, the path to hell is paved with good intentions. Yes, the intent was to help — but the result was to harm.

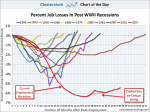

Examples: In keeping her child from failing, a parent winds up ensuring her child never learns how to deal with failure. In promoting home ownership, a government program encourages people to get in over their heads, landing them in foreclosure — and in some cases out on the street — when hard times hit. In that last example, another unintended consequence proved to be that taxpayers had to bail out the banks that were too big to fail.

Oakley provides a fascinating example: “In foreign aid, $2 trillion dollars have been provided to Africa over the past 50 years. As chronicled by economist and former World Bank consultant Dambisa Moyo, a native of Zambia, such aid has resulted in measurably worsened outcomes in a broad variety of areas, supporting despotism and increasing corruption and a sense of dependency in Africans. In some cases, the money has been directly responsible for extraordinary damage. Experienced foreign aid worker Ernesto Sirolli echoes many when he notes that much Western aid arises from narcissistic paternalism and patronization.”

While we may want to help others, it might be more useful to first understand objectively whether our actions will result in the desired state. Or whether we are acting not for outcomes of others, but instead due to narcissistic paternalism, patronization, codependency and/or self righteousness. This would require taking off blinders of bias to see the real results rather than the intended results.

“Are some individuals addicts of their feelings of self-righteousness?” asks Oakley, who notes that altruism bias “seems to grow from or relate to that little studied sense of rightness, of certitude — a tip-of-the-tongue feeling built on a web of biases, influences and perceptions that one thing is beneficial, whereas another is not.”

Nowhere are these questions more needed than in the framework of politics and policy. Filled with rhetoric and emotions, one group or another talks about “helping” this or that constituency — the middle class, the poor, the children. Many groups talk about help, and may really want to help, but few appear to focus on the data about outcomes.

In order to change this, Oakley suggests we “set the stage so that it becomes culturally acceptable, even expected, that one should attempt to quantify objectively purported claims of altruism.”

What happens when programs that are set up to “help someone” instead enable that person or group of people to continue unsustainable activity? In such cases, who gets the real benefit — and who is the real victim?

© JACKIE CUSHMAN

DISTRIBUTED BY CREATORS.COM