In 1987, the Junkyard Dog was one of the top wrestling stars in the world, appearing at WrestleMania III with Hulk Hogan in front of nearly 100,000 people.

Videos by Rare

It was not his most significant achievement.

In 1978, Southern wrestling promoter Bill Watts noticed that when he put black wrestlers in the ring, more black fans would show up to matches. He also noticed that when he put an African-American in the “good guy” role, it was something black fans were eager to see.

When a racist business partner complained about this, Watts’ fellow promoter Grizzly Smith said, “Their money’s green, and it’s the most green thing we’ve seen in a long time.”

Watts wanted more green. So why not make a black man his top star?

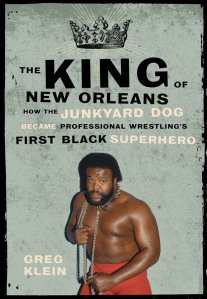

The Junkyard Dog (Sylvester Ritter) became a household name in Louisiana and eventually, the main attraction for Watts’ entire Mid-South promotion (Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi). His character was inspired by the Jim Croce song, “Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown” (“badder than old King Kong, meaner than a junkyard dog”).

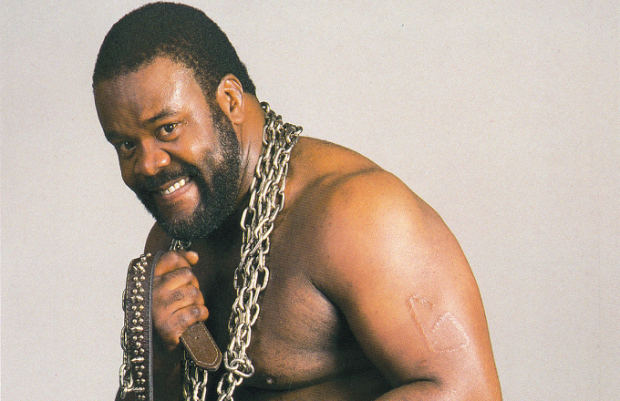

The Junkyard Dog was more than just a wrestler. White fans adored him, but perhaps more significantly, he became a folk hero for black children in Louisiana.

New Orleans has long had one of the largest majority black populations in the country. Antigravity Magazine noted in 2012:

In the 1981-82 academic year, the New Orleans school system asked students which local sports star they’d most like to meet. It was the heyday of Archie Manning’s reign as the Saints’ quarterback. Basketball legend “Pistol” Pete Maravich had just retired from a hall-of-fame career centered on a still-unbroken division scoring record at LSU and five years leading the New Orleans Jazz.

Both these giants received many votes, but New Orleans’ schoolkids overwhelmingly wanted to meet the Junkyard Dog.

Ritter’s biographer Greg Klein explains the cultural and political backdrop of that era in his book, “The King of New Orleans: How the Junkyard Dog Became Professional Wrestling’s First Black Superhero:”

New Orleans, the state of Louisiana, and the rest of the territory were still feeling the backlash of the civil rights era. New Orleans, in particular, had become a troubled city in the ‘70s. Crime was rampant. The police response was to crackdown overwhelmingly on the black community, causing resentment and anger. More than 60 percent of the city’s population was black, but the police and the politicians were almost all white.

Civil rights-style protests and rallies sprang up. In 1977, the city elected its first black mayor, Ernest “Dutch” Morial. New Orleans was ripe for a black wrestler to be its top star; as for the rest of the territory, that question was still open.

It wasn’t an open question for long. The Junkyard Dog’s larger-than-life persona had endeared him to so many fans, black and white, that by the mid-80’s the WWF would come calling. Wrestling columnist Mike Mooneyham observed, “JYD hooked up with the WWF in the mid-’80s and joined Hulk Hogan as one of the few elite performers during that time to pull down six-figure salaries, second only to Hogan as the company’s top babyface.”

Former WWE wrestling announcer Jim Ross, who also worked for Watts during the 80s, said of the Junkyard Dog, “He was the first man of color to headline a territory, so successfully, and it took a lot of courage for him to carry that banner, I think he broke a lot of racial barriers.”

Much of the Junkyard Dog’s calculated success was due to the business savvy of another African-American wrestler, “The Big Cat” Ernie Ladd. It was Ladd’s ability to draw more black fans, along with black wrestler Ray Candy, who first gave Watts the idea to build his company around an African-American.

Making a black man the primary star of a wrestling promotion was unheard of at that time, due primarily to enduring racist attitudes among promoters or even the belief that fans wouldn’t accept it.

But Ladd thought it was smart business and became instrumental in the Junkyard Dog’s success. Greg Klein detailed Ladd’s business collaboration with Watts:

“Bill Watts and Ernie Ladd were students of the statistics… When they got together and began to work on booking ideas, they both knew about the demographics of their region and biggest city. Ladd’s insistence on pushing Ray Candy as the black babyface beating the hated Ernie Ladd didn’t just pay off with the one record Superdome crowd. It confirmed for both men that they needed a black babyface to continue to draw crowds into the future.”

Klein adds, “It was a business decision. Neither man was making a statement for civil rights. To the extent that they were political, they were libertarians; they believed the free market should decide.”

Bill Watts vs. Ernie Ladd, late 60s

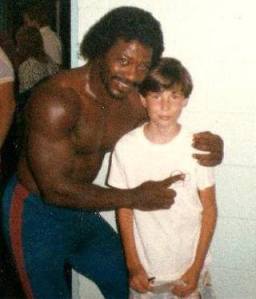

I grew up watching pro wrestling in the 1980s in South Carolina, and unfortunately never saw the Junkyard Dog perform live. I would enjoy watching him in the WWF on television, but as a kid never understood the positive racial and cultural implications of his success. In my child’s mind, I just liked how he would invite kids to dance with him in the ring at the end of his matches as well as his Saturday morning cartoon character.

But I do remember Rocky King, a far less known African-American wrestler who would come to town once a month for shows in a local a high school gymnasium, many of which were full if not sold out.

King never became very famous. He rarely won his matches but seemed to loved entertaining the kids, in and out of the ring. When most of the bigger stars would immediately retreat to their locker rooms after a match, King would stick around, sign autographs and take photos with young fans.

The author with Rocky King, 1986

King was always smiling. Even as he was losing a match, he would be grinning. ‘Why would you smile if you were getting beat up?,’ we thought as children. As an adult, I would learn that King had been homeless before breaking into the wrestling business.

Those young wrestling fans of the mid-80s in Charleston, South Carolina, where King was a star at least once a month, were probably about half black and half white. South Carolina is about 30 percent African-American, but that number probably rose to at least 50 percent at most wrestling events.

No doubt, professional wrestling has a long history of exploiting racial stereotypes for profit. But this unique entertainment business, often laughed off or dismissed, might’ve also been instrumental in improving Southern race relations more than some realize.

And due in no small part to trailblazers like the Junkyard Dog.

Junkyard Dog, early 80s

Greg Keith notes the under-recognized way in which wrestling broke down racial barriers in the South:

There was nowhere in the South in the ‘70s and ‘80s that saw such a mix of races – not to mention sexes and ages – than a wrestling crowd. The multicultural crowd in the old television tapings from Shreveport is inspirational. Black children sit next to white children, and all of them cheer for JYD.

Often you see old white women sitting next to twenty-something black men, all of them cheering and booing in unison. This isn’t the present day when SEC football unites and divides the South based on uniform colors, like purple and gold or crimson and white, rather than skin color.

This was 1980, when most of the people in the audience remembered a time when the races would not have been allowed to sit—or eat or sleep or go to school—with one another.

Keith concludes, “It’s an amazing thing in retrospect, and despite the fact that it was ‘just rasslin,’ it is a history worth remembering and honoring.”