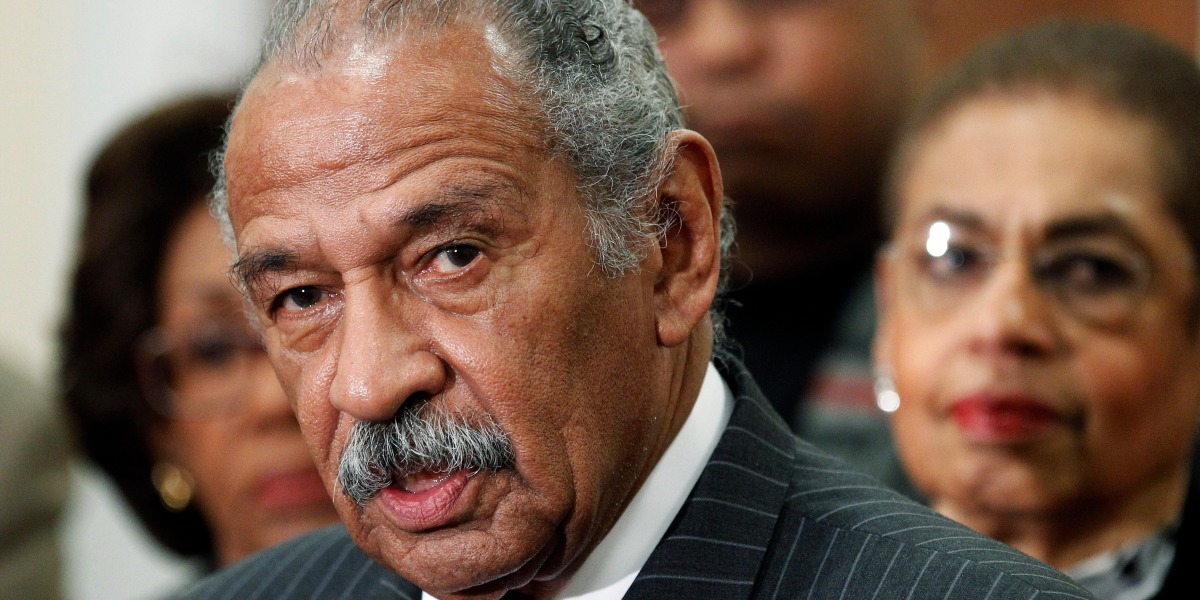

As allegations of sexual harassment, assault and other sundry misconduct by powerful men have spread from Hollywood to Washington, D.C. — aka “Hollywood for ugly people” — the list of the accused is increasingly populated by elected officials. So far we know of allegations against Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.) and Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.), but at this point it would be surprising if more accusations didn’t surface, as female lawmakers and congressional staff have made clear the Hill has an entrenched culture of gross sexual harassment.

Videos by Rare

One reason we haven’t seen more of these stories sooner is settlements. Conyers, for example, reportedly settled with a former staffer for about $27,000 in a wrongful termination case. She was allegedly fired from his congressional office after refusing to “succumb to [his] sexual advances.” Her complaint was made through Congress’s Office of Compliance, and it was via this office that the reported settlement — including a confidentiality agreement that prevented her exposing Conyers’ alleged behavior — was reached. The money reportedly came from Conyers’ office budget.

This is a revealing, but not isolated case. As the Washington Post reported in mid-November, in the past two decades, the “Office of Compliance has paid more than $17 million for 264 settlements and awards to federal employees for violations of various employment rules including … sexual harassment.” The average payout is about $65,000, and the settlements are designed to keep the allegations out of the public eye. In fact, the Post story noted, all settlements “paid from the designated Treasury account” are “confidential.”

While it is understandable that the victims of such violations would want to keep their identities private, the flaws in this system are self-evident: It permits elected officials and other government employees to avoid legal consequences for their misbehavior, from the petty to the criminal, and to do so at the taxpayer’s expense without the taxpayer’s knowledge.

To observe that this arrangement is damaging to responsible government and responsibility, period, should not be controversial. On the contrary, “if there is one issue that can unite all Americans,” writes my conservative colleague Matthew Walther at The Week, “ … it is the principle that sexual harassment carried out by members of Congress and their staff should not be kept secret, and that it is not the taxpayer’s responsibility to pay for it.”

“It is difficult to think of any information whose disclosure would be more in the public interest than the knowledge that Rep. Blueblazer McEntrepreneurship or Sen. Wokeman Goldflake or trusted members of their respective entourages harassed or even assaulted women,” Walther adds. “How it ever came to pass that such cases were not made immediately available to the public is one of those extraordinary mysteries that only Washington could produce.”

Unfortunately, the federal layer is not our only level of government to employ this model of making amends for employee misconduct. Though typically lacking the element of secrecy, a similar dynamic appears in how civil suits alleging police brutality play out: The officer responsible is not held financially responsible.

For instance, in the case of Philando Castile, the black motorist fatally shot by a police officer in my state of Minnesota in 2016, the bereaved family won a civil settlement of about $3 million. As I wrote at the time, that money was good news for the Castiles, who suffered a terrible and utterly unwarranted loss, but it is bad policy, because not a penny of it came from Jeronimo Yanez, the police officer who actually killed Castile, or from the police department that put him on the street with apparently inadequate training. Instead, it came from the League of Minnesota Cities Insurance Trust, which ultimately means it came from Minnesota taxpayers like yours truly.

RARE POV: The civil settlement for Philando Castile’s death is good news but bad policy

That’s normal for this sort of settlement. One study found that out of some $730 million paid out in police settlements over a six-year period by 44 of the largest police departments in the country, just 0.02 percent (less than $150,000) was paid by the cops who actually engaged in misconduct against citizens. The rest was covered by tax dollars. In small municipalities, the same study reported, offending cops “almost never contributed anything to settlements or judgments” in lawsuits brought against them, even when legally required to do exactly that.

The danger of institutionalizing this sort of shift in responsibility is obvious whether we’re dealing with pervy congressmen or aggressive cops. State jobs must not come with a “Get out of jail (and settlement payments) free!” card. It’s time for the guilty in government to pay for their own wrongdoing.