“Books for children have a greater potential for good, or evil, than any other form of literature on Earth.” — Dr. Seuss

Videos by Rare

Today is Read Across America Day, but the celebration will no longer center on Theodor Seuss Geisel, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss, and his famous children’s books. Instead, the late cartoonist‘s work has been slammed for “racial undertones.” Today, on Geisel’s birthday, Dr. Seuss enterprises announced that six Dr. Seuss books will be taken out of circulation due to “hurtful and wrong” imagery: If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, The Cat’s Quizzer, and his debut book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

This news comes after educators in Virginia’s Loudoun County school district announced a plan to de-emphasize Dr. Seuss’ extensive catalog of titles leading up to Read Across America Day: a project by the National Education Association that once promoted children’s literature through commemorating the birth date of Dr. Seuss. President Joe Biden noticeably avoided mentioning Dr. Seuss by name in his official address this morning, honoring Read Across America Day. All of this controversy begs the question: was Dr. Seuss actually a racist?

Re-Examining Dr. Seuss

This week’s furor is not the first time the famed children’s book author has been called into question. In 2019, Katie Ishizuka of Conscious Kid’s Library and Ramón Stephens of the University of California conducted research on diversity in youth literature. They looked at 50 Dr. Seuss books and found that “Of the 2,240 (identified) human characters, there are forty-five characters of color representing 2% of the total number of human characters.” The full study, entitled “The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, AntiBlackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss’s Children’s Books” goes so far as to place the roots of Dr. Seuss’ iconic Cat character in blackface minstrelsy.

In addition to the noted lack of representation, several people of color who do factor into Dr. Seuss stories are wrapped up in insensitive imagery. Of the six titles now being pulled by Dr. Seuss enterprises, there are some clear examples. The Associated Press reports that in And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, an Asian character is pictured “wearing a conical hat, holding chopsticks, and eating from a bowl.” The accompanying text reads: “a Chinese man who eats with sticks.” If I Ran the Zoo portrays “two bare-footed African men wearing what appear to be grass skirts with their hair tied above their heads.”

“Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ catalog represents and supports all communities and families.”

— Dr. Seuss Enterprises

Dr. Seuss’ Anti-Fascist History

The reckoning of recent years has readers and fans wondering about the intent of Dr. Seuss’ more inflammatory images. Certainly, those motives are questionable, but it is surprising to witness the so-called “cancellation” of a deceased author whose anti-fascist beliefs are so well-documented.

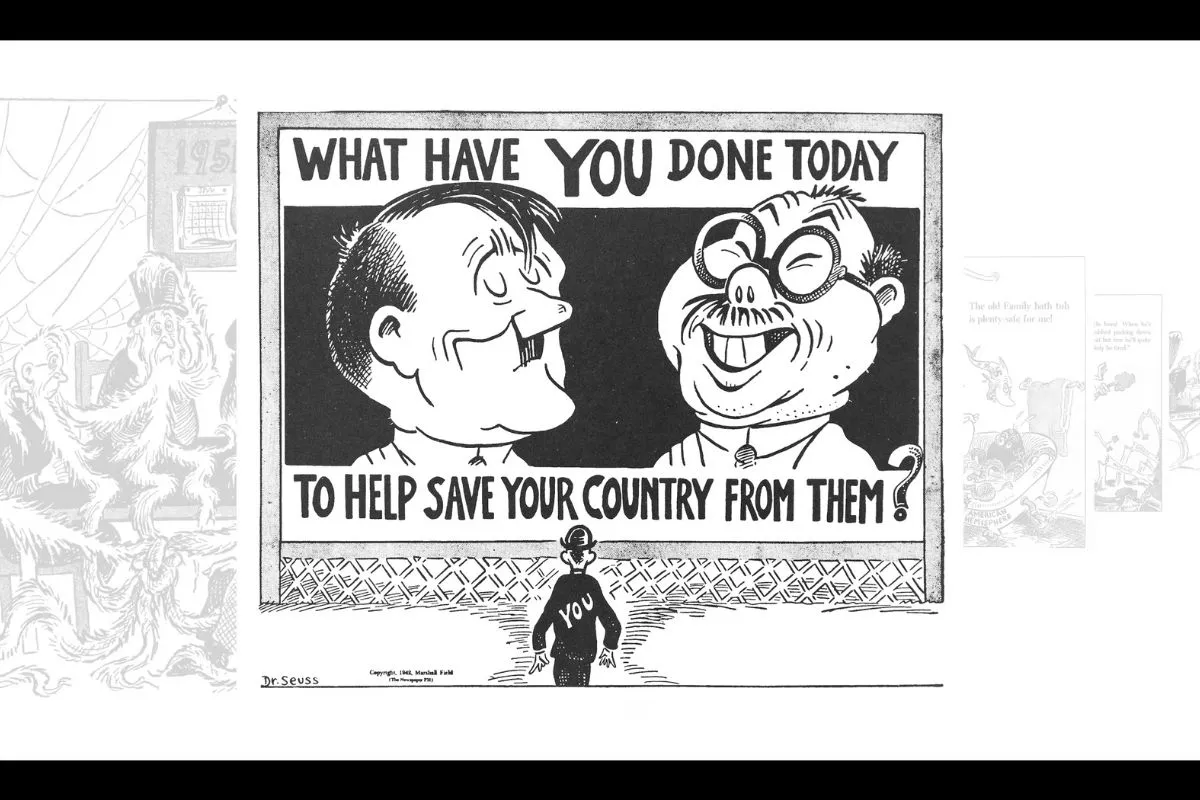

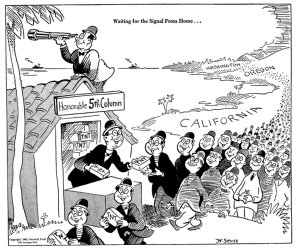

Long before penning beloved classics like The Cat in the Hat, Horton Hears a Who, Green Eggs and Ham, and the environmental call to arms The Lorax, Theodor Seuss Geisel drew political cartoons. He found work at New York City’s outspoken left-wing publication, PM, in the early 1940s. His first cartoon for PM featured a damning depiction of the Italian journalist Virginio Gayda, presenting the reporter a full-on propagandist for the dictator Benito Mussolini. Leading up to America’s ultimate involvement in World War II, Geisel rallied against the so-called “America First” policies which would have prevented entering the conflict. Using his cartoons, Geisel tried to emphasize connections between isolationist politicians like Charles Lindbergh and the dangerous Third Reich. In an interview with his alma mater Dartmouth College, he said:

“I believed the USA would go down the drain if we listened to the America-First-isms of Charles Lindbergh and Senators Wheeler and Nye, and the rotten rot that the Fascist priest Father Coughlin was spewing out on radio. I, probably, was intemperate in my attacks on them. But they almost disarmed this country at the time it was obviously about to be destroyed.”

When the United States did finally enter the conflict in Europe, Dr. Seuss was hired by Treasury Department to design posters and other U.S. war propaganda. In 1943, he officially named Captain Geisel and became commander of the Animation Department of the Army’s First Motion Picture Unit, writing many educational films intended for soldiers’ viewing. Among them, Our Job in Japan, was released publicly after the war under the title Design for the Death. With Geisel’s help, the film had been edited into a study of Japanese culture that considered the origins of the war. Design for Death won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

And though Dr. Seuss is most remembered for his colorful children’s books, his political work is not forgotten. When former president Donald Trump boasted “America First” policies throughout his own administration — going so far as to resurrect the dated term directly — many old Dr. Seuss cartoons made a timely comeback.

Did Dr. Seuss Apologize?

Before becoming a political cartoonist and children’s author, Dr. Seuss utilized his drawing skills in the field of advertising. During that time, he produced ads for Flit bug spray that was objectively racist, presenting people of color as stereotypical savages with exaggerated features, living in tropical climates besieged by mosquitoes. A prideful, colonial spirit certainly defines those old (and indefensible) ads for bug spray. And as you can see in the video above, Theodore Geisel also drew a horrendous four-panel cartoon when he was 25, published in The Judge in 1929, that depicts a slave auction — complete with illustrative blackface and the N-word — for satirical purposes.

Throughout his successful run at PM, many Dr. Seuss cartoons also leaned into exploiting “Asian” tropes in order to drum up support for the war in Japan. These tactics, however, were addressed by Theodor Geisel directly during his lifetime. Although he strongly believed in the war, Geisel spoke to biographers about regretting those cartoons, and certain propaganda works for the Army. Horton Hears a Who is normally read as an, admittedly imperfect, parable about America’s postwar occupation of Japan. Geisel also dedicated the book to “My Great Friend, Mitsugi Nakamura of Kyoto, Japan.”

And Horton Hears a Who was not Dr. Seuss’ only attempt to make amends for racist actions. Most of his work for children deals explicitly with themes of inclusion and tolerance, like How the Grinch Stole Christmas! By distilling topics like prejudice, environmental destruction, and even war, into simpler cartoon terms, Dr. Seuss hoped to impart valuable lessons on young readers. Considering his time working in professional propaganda, he certainly understood how imagery can connect to the soul. As such, In 1978, Dr. Seuss acknowledged that the image of the Asian person in his first book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, should be changed. Although Dr. Seuss Enterprises has now (understandably) flagged the picture as still being offensive, Seuss formally re-designed the character in 1978 to remove the yellow tone of his skin, his pigtail. In the caption, the word “Chinaman” was replaced with “Chinese man.”

In a 2017 op-ed, Taiwanese-American author and illustrator Grace Lin suggested that the complete erasure of such racist images is not necessary. Rather, that they belong in Springfield, Massachusetts’ Dr. Seuss Museum with the appropriate context: “an explanation of Seuss’s journey away from racism.” Since the target audience is children, the discussion of how Dr. Seuss apparently outgrew those harmful beliefs is imperative.

Grace Lin was writing, in particular, about a mural at the museum which, in 2017, still featured the original caricature from And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. As a children’s writer herself, she offers thoughtful analysis surrounding the author’s complicated past. “Dr. Seuss as a man who outgrew his racism and created some of the best works of children’s literature,” she points out. “But I won’t honor one of his offensive drawings unless it’s clearly identified as part of his regrettable past.”

The fact that Dr. Seuss books appeal to extremely young and impressionable readers makes the debate surrounding his legacy entirely important. And while we can absolutely use Read Across America Day to introduce child readers to new authors, the life story of Theodor Seuss Geisel is key to understanding the evolution of his popular work.